Large Language Diffusion Models

Show me an executive summary.

Purpose and Context

Large language models (LLMs) today rely exclusively on autoregressive modeling—predicting the next token from left to right. While successful, this raises a fundamental question: Are core LLM capabilities like scalability, learning from examples, and following instructions inherently tied to this autoregressive approach, or do they arise from deeper principles of generative modeling? This work challenges the assumption that autoregression is necessary by developing and evaluating LLaDA, an 8-billion-parameter language model built entirely on diffusion principles rather than autoregressive generation.

Key Findings

LLaDA demonstrates that diffusion models can achieve performance comparable to leading autoregressive LLMs across diverse benchmarks. Trained from scratch on 2.3 trillion tokens, LLaDA 8B matches or exceeds LLaMA2 7B on nearly all tested tasks and performs competitively with LLaMA3 8B despite using significantly less training data (2.3T vs. 15T tokens). The model shows strong scalability—performance improves predictably as compute resources increase from 10²⁰ to 10²³ FLOPs, matching autoregressive baselines trained on identical data. LLaDA successfully learns from context (few-shot learning) and, after supervised fine-tuning on 4.5 million instruction pairs, follows complex instructions including multi-turn dialogue across multiple languages.

Notably, LLaDA addresses a known weakness of autoregressive models: the "reversal curse," where models trained on "A is B" fail to learn "B is A." On a Chinese poetry completion task requiring bidirectional reasoning, LLaDA achieves 45.6% accuracy on reversal questions compared to only 34.3% for GPT-4o, while maintaining 51.8% accuracy on forward questions (GPT-4o: 82.7%). This suggests LLaDA's bidirectional processing offers advantages for tasks requiring flexible reasoning directions.

What This Means

These results demonstrate that the essential capabilities of large language models—scalability with data and compute, learning from examples, and instruction-following—do not depend on autoregressive architecture. They arise instead from fundamental generative modeling principles: learning probability distributions through maximum likelihood estimation. This challenges a core assumption underlying current LLM development and opens alternative paths for language model research.

The practical implications include offering a flexible trade-off between generation quality and speed (adjustable sampling steps), enabling more robust performance on bidirectional reasoning tasks, and potentially supporting applications where non-sequential generation is advantageous. However, LLaDA currently lacks the inference optimizations (like KV caching) that make autoregressive models efficient, and generation speed remains 1.5–1.8× faster than LLaMA3 only on specific tasks.

Recommendations and Next Steps

Organizations investing in LLM development should consider diffusion models as a viable alternative to autoregressive approaches, particularly for applications requiring bidirectional reasoning or where generation quality-speed trade-offs are valuable. Research teams should explore hybrid architectures combining strengths of both paradigms.

Before production deployment, several gaps need addressing: develop specialized attention mechanisms and position embeddings for diffusion language models; implement system-level optimizations to improve inference efficiency; scale training to datasets comparable to leading autoregressive models (15+ trillion tokens); and apply reinforcement learning alignment, which was not tested here but significantly improves autoregressive model performance.

Further research should investigate adaptive generation length (currently a user-specified parameter), integration with multi-modal data, and compatibility with emerging techniques like chain-of-thought reasoning and agent-based systems.

Limitations and Confidence

High confidence that diffusion models can scale to 8B parameters and achieve competitive performance on standard benchmarks—this is directly demonstrated. Moderate confidence regarding production viability—the model has not undergone the full post-training pipeline (reinforcement learning alignment) that modern LLMs require, and inference efficiency optimizations have not been developed.

Key limitations: training data (2.3T tokens) is substantially smaller than leading models (15T+), making direct performance comparisons imperfect; no specialized architectural optimizations were developed; evaluation primarily focused on English and Chinese, leaving performance on other languages uncertain; and the model architecture uses more parameters in attention layers than necessary due to incompatibility with grouped query attention, slightly increasing computational costs.

The reversal reasoning advantage, while demonstrated on poetry completion, requires validation on broader task categories before concluding it generalizes widely.

Authors: Shen Nie1,2,3∗†^{1,2,3*\dagger}1,2,3∗†, Fengqi Zhu1,2,3∗†^{1,2,3*\dagger}1,2,3∗†, Zebin You1,2,3†^{1,2,3\dagger}1,2,3†, Xiaolu Zhang4‡^{4\ddagger}4‡, Jingyang Ou1,2,3^{1,2,3}1,2,3, Jun Hu4‡^{4\ddagger}4‡, Jun Zhou4^{4}4, Yankai Lin1,2,3‡^{1,2,3\ddagger}1,2,3‡, Ji-Rong Wen1,2,3^{1,2,3}1,2,3, Chongxuan Li1,2,3‡§^{1,2,3\ddagger\S}1,2,3‡§

1^{1}1 Gaoling School of Artificial Intelligence, Renmin University of China

2^{2}2 Beijing Key Laboratory of Research on Large Models and Intelligent Governance

3^{3}3 Engineering Research Center of Next-Generation Intelligent Search and Recommendation, MOE

4^{4}4 Ant Group

{nieshen,fengqizhu,chongxuanli}@ruc.edu.cn

*Equal contribution.

†Work done during an internship at Ant Group.

‡Project leaders.

§Correspondence to Chongxuan Li.

Abstract

The capabilities of large language models (LLMs) are widely regarded as relying on autoregressive models (ARMs). We challenge this notion by introducing

LLaDA, a diffusion model trained from scratch under the pre-training and supervised fine-tuning (SFT) paradigm. LLaDA employs a forward data masking process and a reverse generation process, parameterized by a Transformer to predict masked tokens. It provides a principled generative approach for probabilistic inference by optimizing a likelihood lower bound. Across extensive benchmarks on general tasks, math, code, and so on, LLaDA demonstrates strong

scalability and performs comparably to our self-constructed ARM baselines. Remarkably, LLaDA 8B is competitive with strong LLMs like LLaMA3 8B in

in-context learning and, after SFT, exhibits impressive

instruction-following abilities in case studies such as multi-turn dialogue. Moreover, LLaDA addresses the reversal curse, surpassing GPT-4o in a reversal poem completion task. Our findings show the promise of diffusion models for language modeling at scale and challenge the common assumption that core LLM capabilities discussed above inherently depend on ARMs. Project page and codes:

https://ml-gsai.github.io/LLaDA-demo/.

1 Introduction

In this section, the authors challenge the dominant assumption that autoregressive models are necessary for achieving core large language model capabilities by arguing that these capabilities emerge from general generative modeling principles rather than from the specific autoregressive formulation. They propose that scalability arises from the interaction between Transformers, model and data scale, and Fisher consistency induced by maximum likelihood estimation, not from next-token prediction itself, while in-context learning and instruction-following are intrinsic to conditional generative models broadly. The autoregressive approach does impose limitations, particularly in reversal reasoning tasks where left-to-right generation fails. To demonstrate that LLM capabilities can emerge from alternative generative frameworks, the authors introduce LLaDA, a masked diffusion model employing bidirectional dependencies and variational likelihood optimization. Scaled to 8 billion parameters and trained on 2.3 trillion tokens, LLaDA matches autoregressive baselines on diverse benchmarks, exhibits strong in-context learning comparable to LLaMA3 8B, demonstrates instruction-following after supervised fine-tuning, and overcomes the reversal curse by outperforming GPT-4o on reversal tasks.

Large language models (LLMs) ([1]) fall entirely within the framework of generative modeling. Specifically, LLMs aim to capture the true but unknown language distribution pdata(⋅)p_{\textrm{data}}(\cdot)pdata(⋅) by optimizing a model distribution pθ(⋅)p_{\theta}(\cdot)pθ(⋅) through maximum likelihood estimation, or equivalently KL divergence minimization between the two distributions:

The predominant approach relies on the autoregressive modeling (ARM)—commonly referred to as the "next-token prediction" paradigm—to define the model distribution:

where xxx is a sequence of length LLL, and xix^ixi is the iii -th token. This paradigm has proven remarkably effective ([2, 3, 4, 5]) and has become the foundation of current LLMs. Despite its widespread adoption, a fundamental question remains unanswered: Is the autoregressive paradigm the only path to achieving the core capabilities of LLMs, such as scalability, in-context learning, and instruction-following?

We argue that the answer is not a simple "yes". The key insight overlooked previously is: It is the generative modeling principles (i.e., Eq. (Equation 1)), rather than the autoregressive formulation (i.e., Eq. (Equation 2)) itself, that fundamentally underpin the essential properties of LLMs.

In particular, we argue that scalability is primarily a consequence of the interplay between Transformers ([7]), model size, data size, and Fisher consistency ([8]) induced by the generative principles in Eq. (1), rather than a unique result of the ARMs in Eq. (2). The success of diffusion transformers ([9, 10]) on visual data ([11]) supports this claim. Furthermore, the instruction-following and in-context learning ([4]) capabilities appear to be intrinsic properties of all conditional generative models on structurally consistent linguistic tasks, rather than exclusive advantages of ARMs. In addition, while ARMs can be interpreted as a lossless data compressor ([12, 13]), any sufficiently expressive probabilistic model can achieve similar capabilities ([14]).

However, certain inherent limitations of LLMs can be directly attributed to their autoregressive nature. For instance, the left-to-right generation process restricts their ability to handle reversal reasoning tasks ([15]), highlighting a representative failure in the generalization capabilities of current models.

Motivated by these insights, we introduce LLaDA (Large Language Diffusion with mAsking) to investigate whether the capabilities exhibited by LLMs can emerge from generative modeling principles beyond ARMs, thereby addressing the fundamental question posed earlier. In contrast to traditional ARMs, LLaDA leverages a masked diffusion model (MDM) ([16, 17, 18, 19, 20]), which incorporates a forward data masking process and trains a mask predictor to approximate its reverse process. This design enables LLaDA to construct a model distribution with bidirectional dependencies and optimize a variational lower bound of its log-likelihood, offering a principled and previously unexplored perspective on the core capabilities of LLMs discussed above.

We adopt the standard pipeline of data preparation, pre-training, supervised fine-tuning (SFT), and evaluation, scaling LLaDA to an unprecedented language diffusion of size 8B. In particular, LLaDA 8B was pre-trained from scratch on 2.3 trillion tokens using 0.13 million H800 GPU hours, followed by SFT on 4.5 million pairs. Across diverse tasks, including language understanding, math, code, and Chinese, LLaDA demonstrates the following contributions:

- LLaDA scales effectively to a compute budget of 102310^{23}1023 FLOPs, achieving comparable results to ARM baselines trained on the same data across six tasks, e.g., MMLU and GSM8K.

- The pre-trained LLaDA 8B Base surpasses LLaMA2 7B Base ([21]) on nearly all 15 standard zero/few-shot learning tasks while performing on par with LLaMA3 8B Base ([6]), showcasing effective in-context learning capability.

- LLaDA significantly enhances the ability to follow instructions after SFT, as demonstrated in case studies such as multi-turn dialogue.

- LLaDA effectively breaks the reversal curse ([15]) with consistent performance across forward and reversal tasks. Notably, it outperforms GPT-4o in a reversal poem completion task.

2 Approach

In this section, LLaDA's approach is presented as an alternative to autoregressive language modeling through masked diffusion. Unlike next-token prediction, LLaDA defines a model distribution via forward masking and reverse generation processes, where a mask predictor simultaneously predicts all masked tokens in a sequence. During pre-training, tokens are independently masked at random ratios uniformly sampled from zero to one, and a Transformer is trained to minimize cross-entropy loss on masked positions, which provides an upper bound on negative log-likelihood and ensures principled generative modeling. Supervised fine-tuning follows a similar protocol but masks only response tokens while keeping prompts intact, enabling instruction-following through conditional generation. For inference, LLaDA samples by starting from fully masked sequences and iteratively unmasking tokens through a discretized reverse diffusion process, with flexible remasking strategies balancing quality and efficiency. This formulation enables bidirectional dependencies, overcomes autoregressive limitations like the reversal curse, and provides a theoretically grounded framework for scalable language generation.

In this section, we introduce the probabilistic formulation, along with the pre-training, supervised fine-tuning, and inference procedures for LLaDA, as illustrated in Figure 2.

2.1 Probabilistic Formulation

Unlike ARMs in Eq. (Equation 2), LLaDA defines a model distribution pθ(x0)p_\theta(x_0)pθ(x0) through a forward process and a reverse process ([16, 17, 18, 19, 20]). The forward process gradually masks tokens independently in x0x_0x0 until the sequence is fully masked at t=1t = 1t=1 . For t∈(0,1)t \in (0, 1)t∈(0,1), the sequence xtx_txt is partially masked, with each being masked with probability ttt or remaining unmasked with probability 1−t1 - t1−t . The reverse process recovers the data distribution by iteratively predicting masked tokens as ttt moves from 111 to 000 .

The core of LLaDA is a mask predictor, a parametric model pθ(⋅∣xt)p_\theta(\cdot|x_t)pθ(⋅∣xt) that takes xtx_txt as input and predicts all masked tokens (denoted as M) simultaneously. It is trained using a cross-entropy loss computed only on the masked tokens ([18, 19, 20]):

where x0x_0x0 is a training sample, ttt is a continuous random variable drawn uniformly from [0,1][0, 1][0,1], xtx_txt is sampled from the forward process and LLL is the sequence length. The indicator function 1[⋅]\textbf{1}[\cdot]1[⋅] ensures that the loss is computed only for masked tokens.

Once trained, we can simulate a reverse process (see Section 2.4 for details) parameterized by the mask predictor and define the model distribution pθ(x0)p_\theta(x_0)pθ(x0) as the marginal distribution induced at t=0t = 0t=0 . The loss function in Eq. (3) has been proven to be an upper bound on the negative log-likelihood of the model distribution, making it a principled objective for generative modeling:

Notably, LLaDA employs a masking ratio that varies randomly between 0 and 1 while BERT ([22]) uses a fixed ratio. The subtle differences have significant implications, especially at scale: as shown in Eq. (4), LLaDA is a principled generative model with the potential to perform in-context learning and instruction-following naturally, akin to LLMs. Moreover, its generative perspective implies strong scalability with large data and models as discussed in Section 1. In addition, MaskGIT ([23]) adopts a heuristic training objective, which misses the 1t\frac{1}{t}t1 term compared to Eq. (3), and lacks a theoretical link to maximum likelihood. We emphasize that it is precisely the theoretical foundation of maximum likelihood estimation that motivated us to scale discrete diffusion models for language modeling.

2.2 Pre-training

LLaDA employs a Transformer ([7]) as the mask predictor, similar to existing LLMs. However, LLaDA does not use a causal mask, as its formulation allows it to see the entire input for predictions.

We trained two variants of LLaDA with different sizes: 1B and 8B. We summarize the model architecture of LLaDA 8B and LLaMA3 8B ([6]) here, and details are provided in Appendix B.2. We have ensured consistency in most hyperparameters while making several necessary modifications. We use vanilla multi-head attention instead of grouped query attention ([24]) for simplicity, as LLaDA is incompatible with KV caching, resulting in a different number of key and value heads. Consequently, the attention layer has more parameters, and we reduce the FFN dimension to maintain a comparable model size. Additionally, the vocabulary size differs due to a tokenizer ([4]) adapted on our data.

The LLaDA model is pre-trained on a dataset comprising 2.3 trillion (T) tokens, adhering to a data protocol that aligns closely with existing LLMs ([25, 26]), without the incorporation of any special techniques. The data are derived from online corpora, with low-quality content filtered through manually designed rules and LLM-based approaches. Beyond general text, the dataset encompasses high-quality code, math, and multilingual data. Please refer to Appendix B.1 for more details about datasets. The mixing of data sources and domains is guided by scaled-down ARMs. The pre-training process utilizes a fixed sequence length of 4096 tokens, incurring a total computational cost of 0.13 million H800 GPU hours, similar to ARMs of the same scale and dataset size.

For a training sequence x0x_0x0, we randomly sample t∈[0,1]t\in[0, 1]t∈[0,1], mask each token independently with the same probability ttt to obtain xtx_txt (see Figure 2 (a)) and estimate Eq. (3) via the Monte Carlo method for stochastic gradient descent training. In addition, following [27], to enhance the ability of LLaDA to handle variable-length data, we set 1% of the pre-training data to a random length that is uniformly sampled from the range [1,4096][1, 4096][1,4096].

We adopted the Warmup-Stable-Decay ([28]) learning rate scheduler to monitor the training progress without interrupting continuous training. Specifically, we linearly increased the learning rate from 0 to 4×10−44 \times 10^{-4}4×10−4 over the first 2000 iterations and maintained it at 4×10−44 \times 10^{-4}4×10−4 . After processing 1.2T tokens, we decayed the learning rate to 1×10−41 \times 10^{-4}1×10−4 and held it constant for the next 0.8T tokens to ensure stable training. Finally, we linearly reduced the learning rate from 1×10−41 \times 10^{-4}1×10−4 to 1×10−51 \times 10^{-5}1×10−5 for the last 0.3T tokens. Furthermore, we utilized the AdamW optimizer ([29]) with a weight decay of 0.1, a batch size of 1280, and a local batch size of 444 per GPU. The 8B experiment was executed once, without any hyperparameter tuning.

2.3 Supervised Fine-Tuning

We enhance the capability of LLaDA to follow instructions by supervised fine-tuning (SFT) with paired data (p0,r0)(p_0, r_0)(p0,r0), where p0p_0p0 is the prompt and r0r_0r0 denotes the response. This is the simplest and most basic post-training method for LLMs. Technically, this requires to model the conditional distribution pθ(r0∣p0)p_{\theta}(r_0|p_0)pθ(r0∣p0) instead of pθ(x0)p_{\theta}(x_0)pθ(x0) in pre-training.

The implementation is similar to pre-training. As shown in Figure 2 (b), we leave the prompt unchanged and mask the tokens in the response independently, as done for x0x_0x0 . Then, we feed both the prompt and the masked response rtr_trt to the pre-trained mask predictor to compute the loss for SFT:

where L′L'L′ denotes a dynamic length specified later, and all other notations remain the same as before.

Note that this approach is fully compatible with pre-training. Essentially, the concatenation of p0p_0p0 and r0r_0r0 can be treated as clean pre-training data x0x_0x0, while the concatenation of p0p_0p0 and rtr_trt serves as the masked version xtx_txt . The process is identical to pre-training, with the only difference being that all masked tokens happen to appear in the r0r_0r0 portion.

The LLaDA 8B model undergoes SFT on a dataset comprising 4.5 million pairs. Consistent with the pre-training process, both data preparation and training follow the SFT protocols utilized in existing LLMs ([25, 26]), without introducing any additional techniques to optimize LLaDA's performance. The dataset spans multiple domains, including code, mathematics, and instruction-following. We append ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ tokens to the end of short pairs in each mini-batch to ensure equal lengths across all data. We treat ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ as a normal token during training and remove it during sampling, enabling LLaDA to control the response length automatically. Please refer to Appendix B.1 for more details.

We train for 3 epochs on the SFT data using a similar schedule to the pre-training phase. The learning rate is linearly increased from 0 to 2.5×10−52.5 \times 10^{-5}2.5×10−5 over the first 50 iterations and then kept constant. During the final 10%10\%10% of iterations, it is linearly reduced to 2.5×10−62.5 \times 10^{-6}2.5×10−6. Additionally, we set the weight decay to 0.10.10.1, the global batch size to 256256256, and the local batch size to 222 per GPU. The SFT experiment was executed once, without any hyperparameter tuning.

2.4 Inference

As a generative model, LLaDA can sample new text and evaluate the likelihood of candidate text in a diffusion manner instead of the left-to-right autoregressive fashion.

We begin with the reverse generation process. As illustrated in Figure 2 (c), given a prompt p0p_0p0, we discretize the reverse process to sample from the model distribution pθ(r0∣p0)p_\theta(r_0|p_0)pθ(r0∣p0), starting from a fully masked response. The total number of sampling steps is a hyperparameter, which naturally provides LLaDA with a trade-off between efficiency and sample quality, as analyzed in Section 3.3. We employ uniformly distributed timesteps by default. In addition, the generation length is also treated as a hyperparameter, specifying the length of the fully masked sentence at the beginning of the sampling process. After generation, tokens appearing after the ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ token are discarded. As detailed in Appendix B.5, since both pre-training and SFT are conducted using datasets with variable lengths, the final results are insensitive to this length hyperparameter.

At an intermediate step from time t∈(0,1]t \in (0, 1]t∈(0,1] to s∈[0,t)s \in [0, t)s∈[0,t), we feed both p0p_0p0 and rtr_trt into the mask predictor and predict all masked tokens simultaneously. Subsequently, we remask st\frac{s}{t}ts of the predicted tokens in expectation to obtain rsr_srs, ensuring that the transition of the reverse process aligns with the forward process for accurate sampling ([18, 19, 20]). In principle, the remasking strategy should be purely random. However, inspired by the annealing tricks of sampling in LLMs ([4, 30]), we adopt a low-confidence remasking strategy, where st\frac{s}{t}ts of predicted tokens with the lowest confidence are remarked based on the predictions, same as the approach of [23].

We mention that LLaDA enables flexible sampling. In particular, it supports autoregressive and block diffusion ([31]) sampling directly after the pre-training or SFT processes described above, without requiring any further modifications or training. We provide a detailed analysis in Appendix B.4. Nevertheless, the diffusion sampling (i.e., the reverse generation process) yields the best performance and is adopted as the default throughout this paper, especially for all experiments presented in Section 3.

For conditional likelihood evaluation, we can naturally utilize the upper bound in Eq. (5). However, we find that the following equivalent form ([20]) exhibits lower variance and is more stable:

where LLL is the sequence length of r0r_0r0, lll is uniformly sampled from {1,2,…,L}\{1, 2, \dots, L\}{1,2,…,L}, and rlr_lrl is obtained by uniformly sampling lll tokens from r0r_0r0 without replacement for masking.

We present the training and inference algorithms, along with theoretical details, in Appendix A.

3 Experiments

In this section, LLaDA's performance is rigorously evaluated across scalability, standard benchmarks, and specialized tasks to validate its viability as a diffusion-based language model. LLaDA demonstrates strong scalability up to $10^{23}$ FLOPs, matching autoregressive baselines on six diverse tasks including MMLU and GSM8K, with particularly impressive gains on mathematical reasoning. The pre-trained LLaDA 8B Base surpasses LLaMA2 7B on nearly all 15 benchmarks and competes with LLaMA3 8B, showcasing effective in-context learning despite using significantly less training data. After supervised fine-tuning on 4.5 million pairs, LLaDA exhibits robust instruction-following capabilities including multi-turn dialogue across languages. Crucially, LLaDA breaks the reversal curse, maintaining consistent performance on both forward and backward poem completion tasks while outperforming GPT-4o on reversal reasoning. These results collectively establish that masked diffusion models can scale effectively to 8B parameters, achieving competitive performance with state-of-the-art autoregressive models while offering unique advantages in bidirectional reasoning.

In this section, the formulation and implementation of masked diffusion models (MDMs) for language modeling are detailed through both theoretical foundations and practical algorithms. The training approach defines a forward process that progressively masks tokens in a sequence with linearly increasing probability over time, followed by a reverse process that learns to recover the original data by predicting masked tokens using a cross-entropy loss weighted by the inverse of the masking time. For inference, an equivalent time-free formulation enables stable conditional likelihood estimation with fewer Monte Carlo samples compared to the time-dependent version, while the connection to any-order autoregressive models explains the bidirectional reasoning capabilities observed in practice. The section further introduces classifier-free guidance as a plug-and-play technique to balance prompt alignment and diversity, and provides complete algorithmic descriptions for pre-training, supervised fine-tuning, likelihood evaluation, and two sampling strategies—random remasking and low-confidence remasking—that enable flexible generation quality-speed tradeoffs.

We evaluate the scalability, instruction-following, and in-context learning capabilities of LLaDA on standard benchmarks, followed by analyses and case studies to provide a comprehensive assessment.

3.1 Scalability of LLaDA on Language Tasks

We first investigate the scalability of LLaDA on downstream tasks in comparison with the ARM baselines we constructed. Specifically, at the 1B scale, we ensured that LLaDA and ARM shared the same architecture, data, and all other configurations. At larger scales, we also report results for LLaDA and ARM models of slightly different sizes trained on the same data due to resource limitations. Please refer to Appendix B.2 for more details. We use the pre-training computational cost as a unified scaling metric. For evaluation, we focused on six standard and diverse tasks.

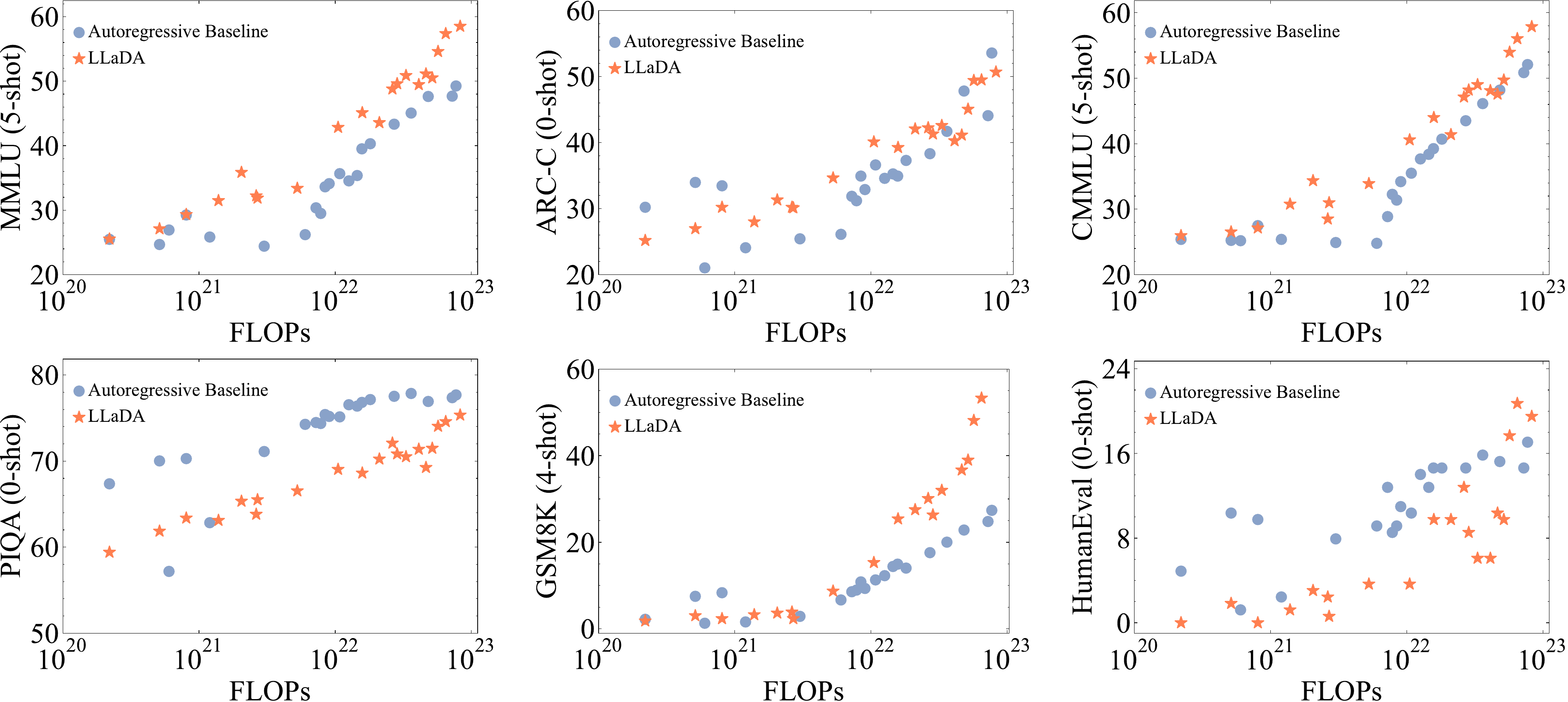

Figure 3 shows that LLaDA demonstrates impressive scalability, with its overall trend highly competitive with ARMs. Notably, on tasks such as MMLU and GSM8K, LLaDA exhibits even stronger scalability. Even on relatively weaker tasks like PIQA, the performance gap with ARMs narrows as scale increases. To account for the influence of outliers, we opted not to fit quantitative curves, avoiding potential misinterpretation. Nevertheless, the results clearly demonstrate the scalability of LLaDA.

Considering LLaDA’s advantages on certain benchmarks, we hypothesize that this performance gain stems from a key architectural difference: while autoregressive models optimize only left-to-right conditional probabilities, LLaDA is trained to consider multiple conditioning directions, as detailed in Appendix A.2, which may offer greater flexibility and lead to better generalization. This hypothesis is motivated by LLaDA’s strong performance on reversal reasoning in Section 3.3 and the ablation studies on sampling strategies in Appendix B.4.

[27] suggests that MDM requires 16 times more computation than ARM to achieve the same likelihood. However, key differences make our findings more broadly applicable. In particular, likelihood is a relatively indirect metric for downstream task performance, and diffusion optimizes a bound of the likelihood, making it not directly comparable to ARM. Additionally, we extended the scaling range from 1018∼102010^{18}\sim10^{20}1018∼1020 FLOPs in [27] to 1020∼102310^{20} \sim 10^{23}1020∼1023 FLOPs in this work.

3.2 Benchmark Results

To comprehensively evaluate the in-context learning and instruction-following capabilities of LLaDA 8B, we conducted detailed comparisons with existing LLMs ([6, 21, 25, 26, 32, 33]) of similar scale. Task selection and evaluation protocols followed existing studies, covering popular benchmarks in general tasks, mathematics, code, and Chinese. Further details are provided in Appendix B.6. For a more direct comparison, we re-evaluated representative LLMs ([6, 21]) in our implementation.

As shown in Table 1, after pretraining on 2.3T tokens, LLaDA 8B Base demonstrates remarkable performance, surpassing LLaMA2 7B Base on nearly all tasks, and is overall competitive with LLaMA3 8B Base. LLaDA shows advantages in math and Chinese tasks. We conjecture that the strengths stem from the same factors as its relatively weaker performance in some tasks—differences in data quality and distribution, largely due to the closed-source situation of LLM datasets.

Notably, we have carefully ruled out the possibility of data leakage by taking GSM8K as an example. First, as shown in Figure 3, LLaDA outperformed ARM baselines regarding GSM8K. Moreover, the conclusion remains on a fully unseen GSM8K-like task ([34]) in Appendix B.8.

Further, Table 2 compares the performance of LLaDA 8B Instruct with existing LLMs. SFT improved LLaDA's performance on most downstream tasks. A few metrics, such as MMLU, showed declines, possibly due to the suboptimal quality of the SFT data. Overall, since we did not perform alignment with reinforcement learning (RL), our results are slightly behind LLaMA3 8B Instruct, though the gaps in many metrics remain small. Notably, even with only SFT, LLaDA demonstrates impressive instruction-following abilities, as detailed in Section 3.4. We leave RL-based alignment for future work.

All results in Section 3 are based on pure diffusion methods, as they achieve better overall performance than approaches incorporating autoregressive components. Specifically, we use Eq. (Equation 6) for conditional likelihood estimation and apply low-confidence remasking for sampling. For LLaDA 8B Instruct, block diffusion style sampling performs better on GSM8K and Math, with scores of 78.6 and 42.2, compared to 69.4 and 31.9 in Table 2. This gain is due to extensive ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ token padding in the SFT data, causing early termination in low-confidence remasking. Please refer to Appendix B.4 for details.

Overall, despite the lack of data transparency, we have made every effort to adopt standardized procedures and introduce diverse tasks, we believe they sufficiently demonstrate the extraordinary capabilities of LLaDA, which is the only competitive non-autoregressive model to our knowledge.

3.3 Reversal Reasoning and Analyses

To quantify the reversal reasoning ([15]) ability of models, we follow the protocol established in [35]. Specifically, we construct a dataset of 496 famous Chinese poem sentence pairs. Given a sentence from a poem, models are tasked with generating the subsequent line (forward) or the preceding line (reversal) without additional fine-tuning. Examples can be found in Appendix B.9. This setting provides a straightforward and more realistic evaluation compared to previous studies ([27, 36]).

As shown in Table 4, LLaDA effectively addresses the reversal curse ([15]), demonstrating consistent zero-shot performance across both forward and reversal tasks. In contrast, both Qwen 2.5 and GPT-4o exhibit a significant gap between the two. The results on forward generation confirm that both ARMs are strong, benefiting from significantly larger datasets and greater computational resources than LLaDA. However, LLaDA outperforms both by a large margin in the reversal task.

We did not design anything special for reversal tasks. Intuitively, LLaDA treats tokens uniformly without inductive bias, leading to balanced performance. See Appendix A.2 for details.

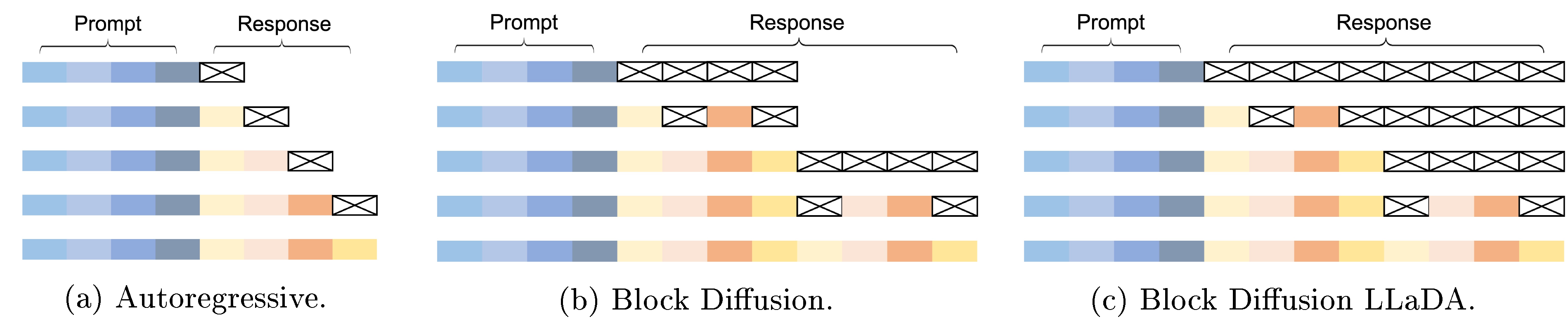

We also analyze the effect of different sampling strategies for LLaDA, including autoregressive sampling, block diffusion ([31]) sampling, and pure diffusion sampling, showing that pure diffusion sampling achieves the best overall performance, as detailed in Appendix B.4.

In addition, we examine LLaDA’s sampling speed and memory consumption, showing that it enables a flexible trade-off between generation quality and speed. See Appendix B.7 for more details.

Classifier-free guidance (CFG) ([37, 27]) is a widely used technique in diffusion models to improve generation quality. To ensure a fair comparison with ARMs, we do not apply CFG to LLaDA in the main text. However, we show that LLaDA is compatible with CFG and consistently benefits from its application. See Appendix B.3 for more details.

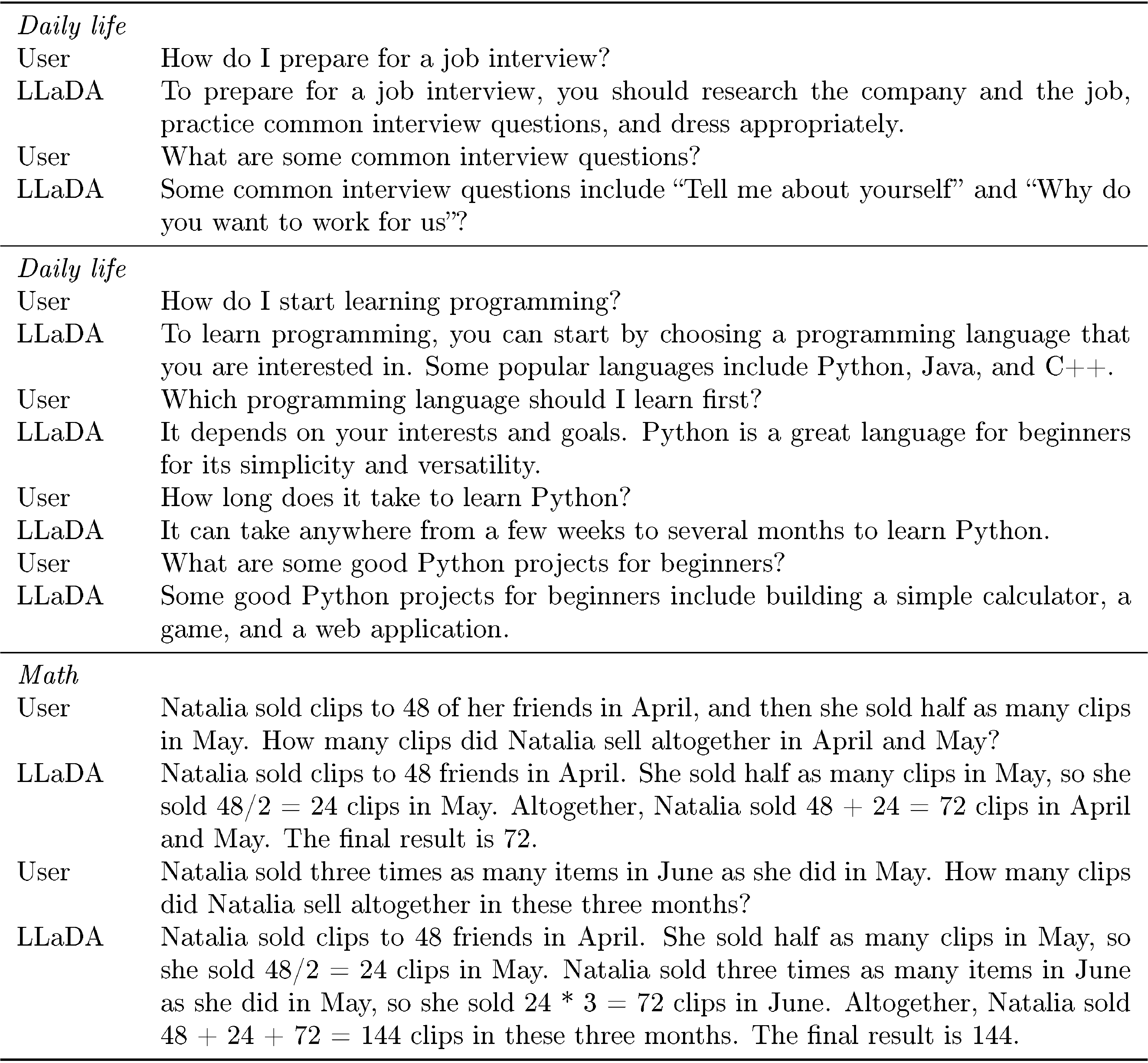

3.4 Case Studies

We present samples generated by LLaDA 8B Instruct in Table 3, showcasing its instruction-following capabilities. First, the table illustrates LLaDA’s ability to generate coherent, fluent, and extended text in a non-autoregressive manner. Second, it highlights the model’s multi-turn dialogue capability, effectively retaining conversation history and producing contextually appropriate responses across multiple languages. Such chat capabilities of LLaDA are impressive, as it departs from conventional ARMs for the first time, to the best of our knowledge. See more case studies in Appendix B.10.

4 Related Work

In this section, diffusion models have achieved remarkable success in visual domains but remained unverified for large-scale language modeling despite extensive research efforts. Two main approaches emerged: continuousizing text data for direct application of continuous diffusion models, and replacing continuous diffusion with discrete processes featuring new forward and reverse dynamics, though both faced scalability challenges with smaller models requiring significantly more compute than autoregressive models to achieve comparable performance. Masked diffusion models, introduced as a special case of discrete diffusion, demonstrated the feasibility of this approach and achieved perplexity comparable to autoregressive models at GPT-2 scale, with theoretical foundations motivating model design and establishing scaling laws for language modeling. This study advances the field by scaling masked diffusion models to an unprecedented 8B parameters from scratch, achieving performance comparable to leading models like LLaMA 3, while parallel work in image generation and other domains like protein generation has shown promise and explored acceleration techniques.

Diffusion models ([38, 39, 40]) have achieved remarkable success in visual domains but remain unverified for large-scale (e.g., models trained with over 102310^{23}1023 FLOPs) language modeling, despite growing interest and extensive research efforts.

A simple approach is to continuousize text data and apply continuous diffusion models directly ([41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51]). Alternatively, some methods model continuous parameters of discrete distributions instead ([52, 53, 54, 55, 56]). However, scalability remains a significant challenge for these approaches. For instance, a 1B model may require 64 times the compute of an ARM to achieve comparable performance ([57]).

Another approach replaces continuous diffusion with discrete processes featuring new forward and reverse dynamics, leading to numerous variants ([58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71]). The original diffusion model paper ([38]) introduced both continuous-state and discrete-state transition kernels under a unified diffusion framework. [16] was among the pioneering works that introduced discrete diffusion models into language modeling, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach. [17] showed that masked diffusion, as a special case of discrete diffusion, achieves perplexity comparable to or surpassing ARMs at GPT-2 scale. [18, 19, 20] established fundamental theoretical results, which motivated our model design, training, and inference (see Appendix A for details). [27] introduced the scaling laws for MDMs in language modeling and explored how MDMs can be leveraged for language tasks such as question answering at the GPT-2 scale. [72] demonstrated the potential of fine-tuning an ARM within the MDM framework. However, the improvements observed by [72] are limited to specific metrics, and their approach does not address the performance achievable through pure diffusion-based training. Concurrent work ([73]) demonstrates the potential of diffusion language models in code generation and highlights their advantages in inference efficiency. Nonetheless, as it is a closed-source product, specific details such as training procedures and sampling methods remain unknown.

In comparison, this study scales MDM to an unprecedented size of 8B parameters from scratch, achieving performance comparable to leading LLMs such as LLaMA 3.

Additionally, a parallel line of work on image generation ([23, 74, 75]) aligns well with the application of MDMs to text data. Moreover, MDMs have also shown promise in other domains such as protein generation ([76, 77]), where they have achieved promising results. Notably, a series of studies ([31, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87]) have explored techniques such as architectural optimization, distillation, and sampling algorithm design to accelerate MDMs sampling.

5 Conclusion and Discussion

In this section, the authors present LLaDA, an 8-billion parameter diffusion language model that achieves performance comparable to leading autoregressive models like LLaMA3 through training from scratch at unprecedented scale. LLaDA demonstrates strong scalability, in-context learning, and instruction-following capabilities while offering unique advantages including bidirectional modeling and enhanced robustness that address key limitations of existing autoregressive language models. Despite these promising results, several limitations remain: the model requires user-specified generation length, computational constraints prevented identical-scale comparisons with autoregressive baselines beyond 10^23 FLOPs, specialized architectural optimizations like KV cache were not implemented, efficient sampling algorithms need further development, and reinforcement learning alignment has not yet been applied. Future work should focus on scaling both model size and training data, exploring multi-modal capabilities, investigating integration with agent systems and prompt tuning, developing more efficient sampling methods, and systematically examining post-training approaches to fully unlock diffusion models' potential for language modeling.

We introduce LLaDA, a diffusion language model trained from scratch with an unprecedented scale of 8B parameters. LLaDA demonstrates strong capabilities in scalability, in-context learning, and instruction-following, achieving performance comparable to strong LLMs such as LLaMA3. In addition, LLaDA offers unique advantages, such as bidirectional modeling and enhanced robustness, effectively addressing the relevant limitations of existing LLMs. Our findings show the promise of diffusion models for language modeling at scale and challenge the common assumption that these essential capabilities are inherently tied to ARMs. These results represent a new paradigm for language modeling and uncover novel insights, demonstrating a high degree of scientific innovation.

Limitations. While promising, the full potential of diffusion models remains to be fully explored. Several limitations of this work present significant opportunities for future research. The generation length is a user-specified hyperparameter. Although LLaDA is insensitive to this hyperparameter as detailed in Appendix B.5, we believe that adopting an adaptive generation length would offer a more efficient solution. Due to computational constraints, direct comparisons between LLaDA and ARMs—such as training on identical datasets—were restricted to a computational budget of less than 102310^{23}1023 FLOPs. To allocate resources for training the largest possible LLaDA model and showcasing its potential, we were unable to scale the ARM baseline to the same extent. Moreover, no specialized attention mechanisms or position embeddings were designed for LLaDA, nor were any system-level architectural optimizations such as KV cache applied. On the inference side, more efficient and controllable ([37, 88, 89]) sampling algorithms remain preliminary. Furthermore, LLaDA has yet to undergo alignment with reinforcement learning ([90, 91]), which is crucial for improving its performance and alignment with human intent.

Looking ahead, both the model scale and the amount of training data for LLaDA remain smaller than those of leading ARM counterparts ([6, 26, 92, 93, 94, 95]), highlighting the need for further scaling to fully evaluate its capabilities. In addition, LLaDA's ability to process multi-modal data remains unexplored. Its impact on prompt tuning techniques ([96]) and integration into agent-based systems ([97, 98]) is still not fully understood. Finally, a systematic investigation into post-training for LLaDA (e.g., O1-like systems ([99, 100])) is needed to further unlock the potential of diffusion language models.

Acknowledgements

In this section, the authors acknowledge the financial support that enabled the research presented in this work. The project received funding from multiple sources in China, including the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant number 92470118, the Beijing Natural Science Foundation under grant number L247030, and the Beijing Nova Program under grant number 20220484044. Additionally, the research was supported by the Ant Group Research Fund. These funding sources collectively provided the necessary resources to conduct the large-scale experiments involved in developing and evaluating LLaDA, an 8 billion parameter diffusion language model trained from scratch, which required substantial computational infrastructure and expertise to achieve performance comparable to leading autoregressive language models.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 92470118); Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. L247030); Beijing Nova Program (No. 20220484044); and Ant Group Research Fund.

Appendix

A. Formulation of Masked Diffusion Models

A.1 Training

MDMs ([16, 17, 18, 19, 20]) define the model distribution pθ(x0)p_\theta(x_0)pθ(x0) in a manner distinct from autoregressive models.

These models introduce a forward process {xt}\{x_t\}{xt} indexed by a time t∈[0,1]t \in [0, 1]t∈[0,1] . This process gradually and independently masks all tokens in the sequence x0x_0x0 . At time t=0t = 0t=0, the data point x0x_0x0 is fully observed with no masks, while for t∈(0,1]t \in (0, 1]t∈(0,1], xtx_txt represents latent variables with varying mask ratios in expectation.

Formally, the conditional distribution of xtx_txt given x0x_0x0 is defined by a fully factorized form:

where the conditional distribution for each token is given by:

Here, M\textrm{M}M denotes the mask token. Intuitively, each token either remains unchanged or is masked, with the probability of being masked increasing linearly as ttt progresses from 000 to 111 . At t=1t = 1t=1, all tokens are guaranteed to be masked, meaning that x1x_1x1 follows a Dirac distribution concentrated on a sequence of fully masked tokens. Notably, the linear masking probability is analogous to but distinct from, the noise schedule in continuous diffusion models [38, 39, 40]. This linearity is motivated by the assumption that the information in the text is proportional to the number of tokens on average, making it reasonable to lose information linearly during the forward process.

The forward process is not only reversible but also corresponds to a reverse process that is fully factorized across all tokens. The reverse process, from time t=1t = 1t=1 to 000, generates new data from sequences of fully masked tokens. The conditional distribution for the reverse process, for 0≤s<t≤10 \leq s < t \leq 10≤s<t≤1, is factorized as:

where the conditional distribution for each token is:

Thus, the key function to estimate is the conditional distribution q0∣t(xsi∣xt)q_{0|t}(x_s^i|x_t)q0∣t(xsi∣xt), which predicts the original token if it is masked in the input xtx_txt . This is analogous to the data prediction form in continuous diffusion models.

As proven in [20], an equivalent yet time-free parameterization can be derived as:

where xtUMx_t^{\textrm{UM}}xtUM denotes the collection of unmasked tokens in xtx_txt, which is identical to the corresponding tokens in the original data x0x_0x0 since unmasked tokens are solely determined by x0x_0x0 and are independent of time ttt . Intuitively, this implies that estimating the data prediction function is equivalent to estimating the conditional distributions on clean data, which is time-invariant. Consequently, the time ttt need not be provided as input to the parametric model.

Although the development of masked diffusion is nontrivial, the implementation is straightforward. We first introduce the mask predictor, a parametric model pθ(⋅∣xt)p_{\theta}(\cdot|x_t)pθ(⋅∣xt) (e.g., a Transformer without causal mask), which takes xtx_txt for any ttt as input and predict all masked tokens simultaneously. Then, we define the model distribution pθ(x0)p_\theta(x_0)pθ(x0) as follows: starting with x1x_1x1 as a sequence of fully masked tokens, we simulate an approximate reverse process parameterized by pθ(⋅∣xt)p_{\theta}(\cdot|x_t)pθ(⋅∣xt) from t=1t = 1t=1 to 000 . The marginal distribution induced at t=0t = 0t=0 then represents the model distribution pθ(x0)p_\theta(x_0)pθ(x0).

Formally, the mask predictor is trained using a cross-entropy loss with masking:

where x0x_0x0 is sampled from the training data, ttt is sampled uniformly from [0,1][0, 1][0,1], and xtx_txt is sampled from qt∣0(xt∣x0)q_{t|0}(x_t| x_0)qt∣0(xt∣x0) . The indicator function 1[⋅]\textbf{1}[\cdot]1[⋅] ensures that the cross-entropy loss is computed only for masked tokens. In [18, 19, 20], it has been proven that the loss function L(θ)\mathcal{L}(\theta)L(θ) is an upper bound on the negative log-likelihood of the model distribution:

In summary, this principled approach trains a generative model by progressively masking tokens during a forward process and learning to recover the data distribution during a reverse process, all under the (approximate) maximum likelihood estimation framework.

A.2 Inference

The cross-entropy loss in Eq. (10) has several equivalent forms [20]. The first one is given by

where lll is uniformly sampled from {1,2,…,L}\{1, 2, \dots, L\}{1,2,…,L}, and xlx_lxl is obtained by uniformly sampling lll tokens from x0x_0x0 without replacement for masking. Despite masking exactly lll tokens is different from masking each token independently with probability ttt, these two masking methods lead to equivalent results in expectation [20].

While Eq. (10) and Eq. (11) share the same expectation, their variances differ. Intuitively, in Eq. (Equation 10), we expect xtx_txt to have a fraction of ttt tokens masked. However, the randomness of the forward process (i.e., Eq. (7)) often causes deviations, especially when xtx_txt contains few tokens. In contrast, in Eq. (11), the fraction of masked tokens in xlx_lxl is deterministically lL\frac{l}{L}Ll . While a theoretical analysis depends on the data distribution, empirical results show that Eq. (10) requires over 1000 Monte Carlo estimates for stable results, whereas Eq. (11) achieves stability with only 128 estimates. In addition, we can simply modify Eq. (Equation 11) to its conditional version (i.e., Eq. (6)) based on Eq. (5).

Any-order autoregressive models (AO-ARM) [59, 101, 102] characterize the joint distribution autoregressively for all possible orders π\piπ of the LLL variables. To learn such a distribution, an AO-ARM utilizes a weight-sharing neural network to model all univariate conditionals and employs mask tokens to represent absent variables. During training, the expected negative log-likelihood over the uniform distribution of all orders UπU_\piUπ is minimized:

Intuitively, x0π(<i)x_0^{\pi(<i)}x0π(<i) can be understood as a masked token xtx_txt with index in π(≥i){\pi(\geq i)}π(≥i) being masked. It can be further proved that Eq. (12) is equivalent to Eq. (10). This connection explains the bidirectional reasoning capabilities of LLaDA, even though it was never used explicitly in the inference procedure.

In addition, [27] introduces unsupervised classifier-free guidance (CFG), a plug-and-play technique that balances alignment with prompts and text diversity. Specifically, unsupervised CFG employs the following modified mask predictor for inference:

where mmm is a mask sequence of the same length as p0p_0p0 and www is a tunable hyperparameter that controls the strength of p0p_0p0. To ensure a fair comparison with ARMs, we do not apply CFG to LLaDA in the main text. However, as demonstrated in Appendix B.3, LLaDA is fully compatible with CFG and consistently exhibits improved performance when it is applied.

A.3 Algorithms

In this section, we present the training and inference algorithms. Specifically, we introduce the pre-training and supervised fine-tuning algorithms in Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2, respectively. In addition, the likelihood evaluation algorithm is provided in Algorithm 3. Finally, we present the reverse generation process in Algorithm 4 and Algorithm 5, which correspond to the random remasking and the low-confidence ([23]) remasking strategy, respectively.

B Experiments

In this section, the authors detail the experimental setup and evaluation of LLaDA, a masked diffusion language model, covering data collection, training procedures, and comprehensive benchmarking. The pre-training corpus combines diverse sources totaling over 11% Chinese, 61% English, and 28% code, with rigorous filtering and quality control, while the supervised fine-tuning dataset includes 1 million human-annotated and 3.5 million synthetic samples. Training employs AdamW optimization with a Warmup-Stable-Decay scheduler across 1B and 8B parameter variants, demonstrating favorable scaling laws compared to autoregressive baselines. Ablation studies reveal that classifier-free guidance consistently improves performance, pure diffusion sampling outperforms autoregressive and block diffusion strategies, and low-confidence remasking surpasses random remasking. Evaluation across general reasoning, mathematics, code generation, and Chinese understanding benchmarks shows LLaDA achieves competitive or superior performance to LLaMA3 while offering flexible speed-quality trade-offs, with sampling efficiency analyses confirming up to 1.8x throughput gains on certain tasks despite lacking KV cache optimizations.

B.1 Data Collection and Preprocessing

In this section, we first introduce the data collection and filtering processes for both pre-training and SFT. We then describe how LLaDA leverages these datasets during training.

Our pre-training corpus is constructed from diverse publicly available sources, including web data, books, academic papers, social media, encyclopedias, mathematics, and code, with approximately 11% Chinese, 61% English, and 28% code. The data cleaning process involves PDF text extraction, deduplication, and harmful content filtering. To further ensure quality, we fine-tune a BERT ([22]) model for automated data quality annotation, enabling the selection of higher-quality samples. Our SFT dataset consists of 1 million human-annotated samples and 3.5 million synthetic samples, generated using methods similar to those proposed in [103, 104].

We concatenate the collected documents in the pre-training corpus and segment the text into fixed-length sequences according to the predefined sequence length.

For SFT, a dynamic sequence length strategy is employed, where ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ tokens are appended to the end of shorter pairs to ensure uniform sequence lengths across all samples within each mini-batch. Notably, the padding ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ tokens are treated as part of the response, i.e., masked and included in the training objective. The ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ tokens are removed from the generated outputs during sampling. This strategy ensures that the model learns to control the length of its responses by generating ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣, enabling the response length to align effectively with the given prompt.

In addition, for nnn-turn dialogues (p00,r00,p01,r01,…,p0n−1,r0n−1)(p_0^0, r_0^0, p_0^1, r_0^1, \dots, p_0^{n-1}, r_0^{n-1})(p00,r00,p01,r01,…,p0n−1,r0n−1), we treat it as nnn single-turn dialogue pairs, i.e., (p00,r00),(p00r00p01,r01),…,(p00r00p01r01…p0n−1,r0n−1)(p_0^0, r_0^0), (p_0^0r_0^0p_0^1, r_0^1), \dots, (p_0^0r_0^0p_0^1r_0^1\dots p_0^{n-1}, r_0^{n-1})(p00,r00),(p00r00p01,r01),…,(p00r00p01r01…p0n−1,r0n−1) and randomly sample one. This data partitioning strategy not only equips LLaDA with multi-turn dialogue capabilities but also aligns with the above ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ padding strategy.

B.2 Details about Model Training

This section provides the training details of LLaDA and the corresponding ARM baselines.

Firstly, for efficiency, we trained an ARM and an MDM, both with 1.5B parameters and identical architectures. Additionally, we scaled the MDM to 8B parameters. Due to computational resource constraints, we did not train an 8B autoregressive model with the same architecture. Instead, we utilized our previously trained 7B autoregressive model for comparison. These four models are utilized in the scalability analysis in Section 3.1.

We adopted a Transformer architecture similar to LLaMA [6, 21] for the ARMs and MDMs we trained. Specifically, we employ RMSNorm [105] to stabilize training, use SwiGLU [106] as the activation function to enhance non-linearity, and integrate RoPE [107] for more expressive positional encoding. Table 5 provides an overview of the model architectures.

For the 1B and 7B ARM baselines, as well as the 1B and 8B LLaDA models, we utilized the AdamW optimizer ([29]) with a weight decay of 0.1 and adopted the Warmup-Stable-Decay ([28]) learning rate scheduler. The learning rate was linearly increased from 0 to the maximum value over the first 2000 iterations and then held constant. For LLaDA 8B, to ensure stable training, the learning rate was reduced once during pre-training, as detailed in Section 2.2. For the 1B ARM baseline and both the 1B and 8B LLaDA models, the maximum learning rate is set to 4×10−44 \times 10^{-4}4×10−4 with a batch size of 1280, without any hyperparameter tuning. For the 7B ARM baseline, the maximum learning rate is set to 4.2×10−44.2 \times 10^{-4}4.2×10−4 with a batch size of 4224, both selected via grid search.

Additionally, we employ the widely used 6ND6ND6ND formulation [108, 109] to calculate the training FLOPs in Figure 3, where NNN represents the number of non-embedding parameters, and DDD denotes the total number of training tokens. The detailed results corresponding to Figure 3 are provided in Table 18 and Table 19.

B.3 Ablation on Classifier-free Guidance

This section presents an ablation study on classifier-free guidance (CFG). Theoretical details about CFG can be found in the Appendix A.2.

For simplicity, we select six representative benchmarks, including ARC-C, HellaSwag, TruthfulQA, WinoGrande, PIQA, and GPQA, and conduct experiments using LLaDA 8B Base. We search the CFG scale in {0.5,1,1.5,2}\{0.5, 1, 1.5, 2\}{0.5,1,1.5,2} for each task and report the best result. As shown in Table 6, CFG consistently improves the performance of LLaDA. We emphasize that, to ensure a fair comparison with ARMs, CFG is not used in the main results reported in the paper.

B.4 Details and Ablation on Sampling Strategies

In this section, we first introduce the different sampling strategies supported by LLaDA. We then present ablation studies to evaluate the performance of these sampling strategies.

Flexible Sampling Strategies. In Section 2.4, Figure 2 (c) illustrates the reverse generation process of LLaDA. As shown in Figure 4, in addition to the reverse generation process, LLaDA also supports autoregressive and block diffusion ([31]) sampling directly after the pre-training or SFT stages, without requiring any further modifications or retraining. Block diffusion sampling applies the origin reverse process within each block and the autoregressive sampling across blocks. In the original block diffusion process, the sequence length varies dynamically. As shown in Figure 4 (c), LLaDA can also adopt a fixed-length block diffusion strategy, which we refer to as block diffusion LLaDA, also known as semi-autoregressive remasking.

Experimental Setup. We evaluate different sampling strategies using both LLaDA 8B Base and LLaDA 8B Instruct for comprehensive analysis. For LLaDA 8B Base, we use the five benchmarks in Table 1 that are evaluated based on sampling rather than likelihood estimation. For LLaDA 8B Instruct, we use the seven metrics in Table 2, excluding MMLU and HellaSwag, since these two tasks only require the model to generate a single token (i.e., A, B, C, or D). In all settings, one token is generated per sampling step. For autoregressive and block diffusion sampling, generation terminates when the ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ token is produced. For block diffusion LLaDA (i.e., semi-autoregressive remasking) and pure diffusion sampling, the generation length is fixed at 1024 for LLaDA 8B Base, while for LLaDA 8B Instruct, it is tuned from 64, 256, 512 to balance efficiency and performance. Low-confidence remasking is applied to intra-block diffusion sampling in both block diffusion and block diffusion LLaDA, as well as to pure diffusion sampling. We also test different block lengths for LLaDA 8B Base. For LLaDA 8B Instruct, we only evaluate block length 32 for efficiency, as it yields the best results on LLaDA 8B Base.

Additionally, for LLaDA 8B Instruct, due to heavy padding of ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ tokens in the SFT data (as detailed in Appendix B.1), we observe that under pure diffusion sampling, the proportion of ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ tokens in model outputs becomes very high. This leads to extremely short generations and degrades model performance. To mitigate this issue, for HumanEval, MBPP, GSM8K, Math, and GPQA, we set the confidence score of the ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ token to zero during pure diffusion sampling. This adjustment helps maintain an appropriate ratio of ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ tokens during generation.

Finally, we conduct ablation studies to analyze the effects of random and low-confidence remasking strategies using the pure diffusion sampling. For efficiency, we use LLaDA 8B Base with generation length and sampling steps set to 256 in this analysis.

Results. As shown in Table 7, for block diffusion sampling, overall performance improves as the block length increases. Moreover, both Table 7 and Table 8 show that block diffusion sampling consistently outperforms autoregressive sampling, and block diffusion LLaDA sampling further improves upon standard block diffusion sampling. Finally, pure diffusion sampling achieves the best overall performance.

In addition, Table 9 shows that the low-confidence remasking strategy consistently outperforms the random remasking strategy. We hypothesize that low-confidence remasking functions similarly to the annealed sampling method used by default in ARMs, improving accuracy by reducing the diversity of generated sentences.

We discover that autoregressive sampling leads to very poor performance for LLaDA 8B Instruct. This is because each SFT data is a complete sentence, so given a sequence length, LLaDA 8B Instruct tends to generate a full sentence within that length. In contrast, LLaDA 8B Base does not suffer from this issue, as the pre-training data consists of truncated documents (as detailed in Appendix B.1) and the model is trained with random sequence lengths (as detailed in Section 2.2). As a result, when given a short sequence length, LLaDA 8B Base tends to generate only part of a sentence, which can then be used as a prefix to continue generation.

Setting the block length to 8 in Table 8 further improves the GSM8K score from 77.5 to 78.6.

B.5 Ablation on Generated Length

In this section, we conduct ablation studies on the generated length.

To ensure fairness, for each setting, we set the number of sampling steps equal to the generated length, ensuring that in each sampling step, just one tokens are transferred from the mask to the text. We conduct experiments using LLaDA 8B Base.

As reported in Table 10, the results are not sensitive to the length hyperparameter.

B.6 Standard Benchmarks and Evaluation Details

In this section, we introduce the benchmarks we used and present the details of our evaluation process.

Following standard LLM [25, 26] evaluation practices, we assess LLaDA across four dimensions:

General ability: MMLU [110], BBH [111], ARC-C [112], Hellaswag [113], TruthfulQA [114], WinoGrande [115] and PIQA [116].

Math and science ability: GSM8K [117], Math [118] and GPQA [119].

Code generation: HumanEval [120], HumanEval-FIM [121] and MBPP [122].

Chinese understanding: CMMLU [123] and C-Eval [124].

For all the aforementioned benchmarks, we follow the widely adopted evaluation process [125] used in LLM assessments, primarily employing conditional likelihood estimation and conditional generation. Specifically, for certain benchmarks, a prompt and multiple candidate answers are provided, and the model is required to compute each candidate's conditional likelihood. The candidate with the highest likelihood is then selected as the model’s final answer, and accuracy is used as the evaluation metric. For the remaining benchmarks, the model generates responses based on the given prompt, and performance is evaluated using metrics such as exact match and other relevant criteria.

For the base model, we use conditional likelihood estimation for MMLU, CMMLU, C-Eval, ARC-C, Hellaswag, TruthfulQA, WinoGrande, PIQA, and GPQA, while the remaining benchmarks are evaluated using conditional generation. For the instruct model, we evaluate all benchmarks using conditional generation.

For the base model, we use the widely adopted open-source evaluation framework lm-evaluation-harness [125], except for the HumanEval-FIM metric, which is not supported by the framework. For HumanEval-FIM on the base model and all evaluation metrics on the instruct model, we use an internal evaluation library. We choose the internal library as lm-evaluation-harness shows greater deviation from the LLaMA3 results reported by [25], relative to our internal evaluation.

For benchmarks evaluated via conditional likelihood estimation, we use Monte Carlo estimation to approximate Eq. (6) for LLaDA. Since MMLU, CMMLU, and C-EVAL only require the likelihood of a single token, a single Monte Carlo estimate is sufficient for these benchmarks. For all other benchmarks, we find that 128 Monte Carlo samples are adequate to produce stable results.

For benchmarks evaluated using conditional generation, we apply pure diffusion sampling with a low-confidence remasking strategy to both LLaDA Base and LLaDA Instruct. For LLaDA Base, we set both the generation length and the number of sampling steps to 1024. For LLaDA Instruct, the number of sampling steps is set equal to the answer length, which is configured as follows: 3 for MMLU and HellaSwag, 64 for GPQA, 256 for MBPP and MMLU-Pro, and 512 for HumanEval, GSM8K, Math, and ARC-C. As detailed in Appendix B.4, for HumanEval, MBPP, GSM8K, Math, and GPQA, we set the confidence of the ∣EOS∣|\text{EOS}|∣EOS∣ token to zero during sampling for LLaDA Instruct.

B.7 Analysis of Sampling Efficiency

In this section, we first analyze the sampling efficiency of LLaDA, including both sampling speed and memory consumption. We then discuss potential optimizations to further improve its efficiency.

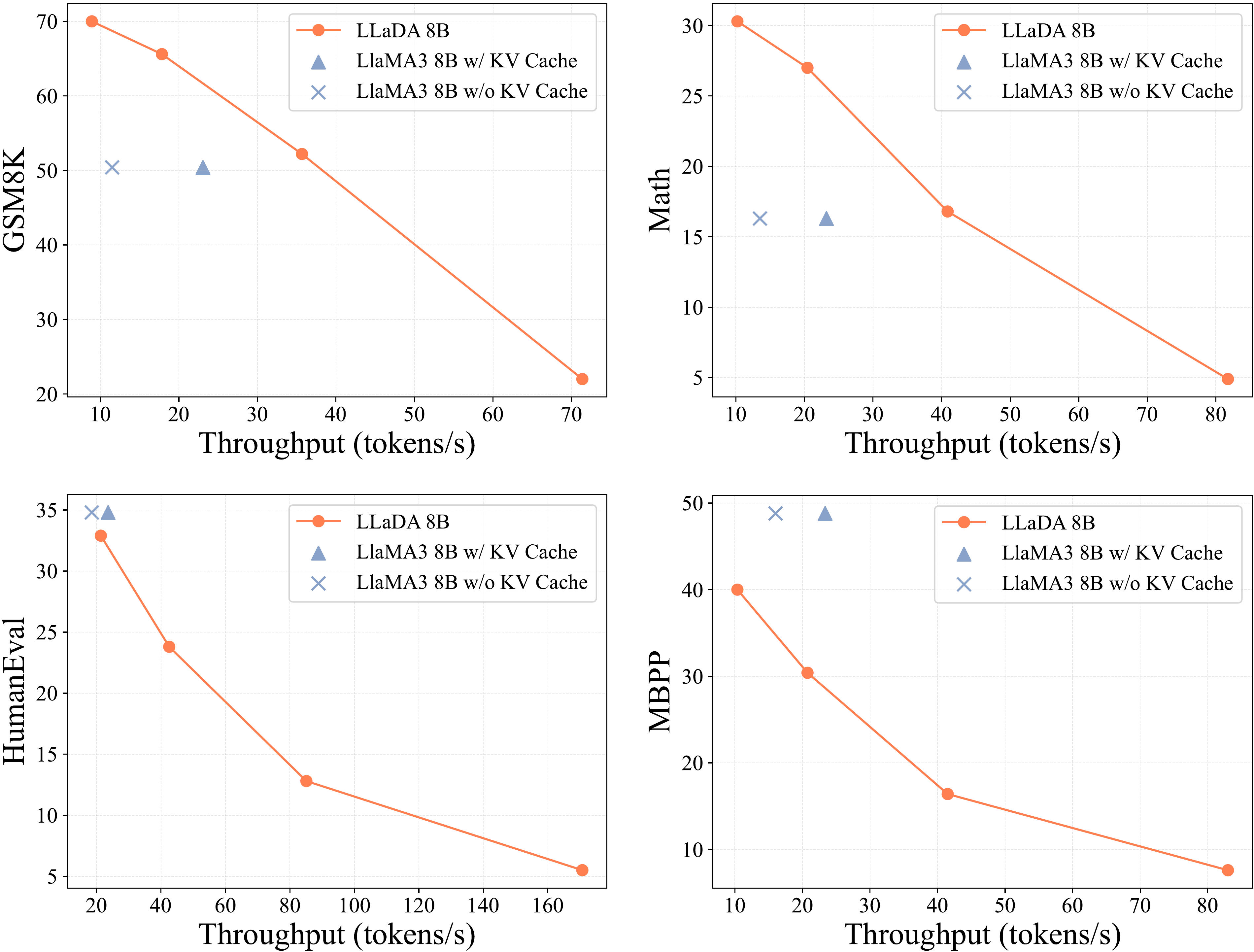

We use four representative open-ended generation benchmarks for sampling speed analysis: GSM8K, Math, HumanEval, and MBPP. We use the widely adopted throughput metric to measure generation speed, defined as the number of tokens generated per second. We compare LLaDA 8B Base and LLaMA3 8B Base, both using bfloat16 precision. All experiments in this section were conducted on a single A100-80GB GPU with a batch size of 1. For LLaDA, the output length is fixed to 256 tokens across all four benchmarks.

Figure 5 shows that LLaDA enables a flexible trade-off between generation quality and speed by adjusting the number of sampling steps. Specifically, on the GSM8K and Math datasets, LLaDA 8B Base achieves comparable performance to LLaMA3 8B Base while delivering 1.5 and 1.8 times higher throughput, even though LLaMA3 uses KV Cache and LLaDA operates without any inference optimization techniques. For the HumanEval benchmark, LLaDA 8B Base performs comparably to LLaMA3 8B Base when the throughput is matched. On the MBPP benchmark, LLaDA 8B Base lags behind LLaMA3 8B Base.

For LLaMA3, the acceleration benefit provided by KV caching is notably weaker on the HumanEval dataset, which can be attributed to its relatively short prompt lengths. Specifically, the average prompt lengths for GSM8K, Math, MBPP, and HumanEval are 894, 680, 628, and 132 tokens, respectively.

Table 11 compares of memory consumption between LLaDA 8B Base and LLaMA3 8B Base. To avoid variations in generation length caused by differences in training data, we fix both the input and output token lengths during the memory analysis. For LLaDA, memory usage remains constant regardless of the number of sampling steps. Its memory consumption is comparable to LLaMA3 8B Base without KV cache, but slightly higher than with KV cache.

We emphasize that the goal of this study is not to propose a model that is faster than ARMs. Instead, we aim to show the promise of diffusion models for language modeling at scale and challenge the common assumption that core LLM capabilities such as scalability, in-context learning, and instruction-following are inherently depend on ARMs. A substantial body of research ([31, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87]) has focused on improving the generation efficiency of MDMs through algorithmic or architectural innovations. We leave similar efficiency-oriented exploration for LLaDA to future work.

B.8 Evaluation on iGSM Dataset

To further assess the mathematical capabilities of LLaDA, we test its performance on iGSM [34], an infinite, synthetic GSM8K-like dataset. iGSM is generated via specific rules, with parameters that control the difficulty of problems (i.e., the number of solution steps). For evaluation consistency, we append "#### $answer" to the final solution, adhering to the GSM8K format. Below is an example with solution steps set to 4:

Since there are slight differences between GSM8K and iGSM (e.g., the use of a mod 5 algorithmic system), we follow [34] and provide a system prompt along with four-shot question-answer pairs for each problem.

For solution steps ranging from 4 to 6, we generate 100 questions for each case and report the corresponding accuracy in Table 12. As shown in the table, LLaDA 8B Base demonstrates significant and consistent advantages over LLaMA3 8B Base on unseen mathematical problems, aligning with the results in Table 1.

B.9 Poem Completion Tasks

In this section, we present examples from our poem completion dataset as follows.

Example 1:

Prompt: 窈窕淑女的下一句是什么?直接输出句子即可。

Answer: 君子好逑。

Example 2:

Prompt: 不拘一格降人才的上一句是什么?直接输出句子即可。

Answer: 我劝天公重抖擞。

B.10 More Case Studies

In this section, we present additional case studies of LLaDA 8B Instruct. First, Table 13 shows the sampling process of the block diffusion LLaDA sampling, while Table 14 depicts the sampling process for multi-turn dialogues with random remasking. Additionally, Table 15 and Table 16 provide further examples of single-turn and multi-turn dialogues. Finally, Table 17 presents examples of poem reversal completions where the LLaDA 8B Instruct model succeeds, in contrast to the failure of GPT-4o.

C Impact Statement

In this section, the authors acknowledge that while their work demonstrates the viability of diffusion models for large-scale language modeling and challenges the assumption that core capabilities like scalability, in-context learning, and instruction-following are exclusive to autoregressive models, this advance opens new avenues for exploring alternative probabilistic paradigms in natural language processing with potential applications in conversational AI, code generation, and complex reasoning tasks. However, diffusion language models inherit similar societal concerns as traditional large language models, including the environmental impact of large-scale training, the potential for misuse in generating harmful content, and the amplification of biases present in training data. The authors emphasize that addressing these challenges is critical to ensuring the responsible development and deployment of diffusion language models as they transition from research curiosities to practical tools.

Our work shows the promise of diffusion models for language modeling at scale and challenges the common assumption that core LLM capabilities such as scalability, in-context learning, and instruction-following are inherently dependent on ARMs. Our findings open new avenues for exploring alternative probabilistic paradigms in natural language processing, with potential applications in conversational AI, code generation, and complex reasoning tasks.

However, diffusion models, like traditional LLMs, raise similar societal concerns. These include the environmental impact of large-scale training, the potential misuse for generating harmful content, and the amplification of biases present in training data. Addressing these challenges is critical to ensuring the responsible development and deployment of diffusion language models.

References

In this section, the references catalog the extensive research ecosystem underpinning large language models and diffusion-based approaches. The citations trace the evolution from foundational transformer architectures and early language models like GPT through modern open-source efforts such as LLaMA, Qwen, and DeepSeek, while documenting the rise of chat-optimized systems like ChatGPT. A substantial portion addresses discrete diffusion models applied to text generation, spanning masked generative transformers, score matching techniques, continuous-time formulations, and hybrid autoregressive-diffusion architectures. Additional references cover acceleration methods including distillation and fast sampling schedules, alongside guidance mechanisms for controllable generation. Evaluation benchmarks for measuring multitask understanding (MMLU, CMMLU, C-Eval), reasoning (GSM8K), code generation (HumanEval), and commonsense reasoning (ARC, PIQA) are documented. The collection reflects a convergence of autoregressive and diffusion paradigms, emphasizing scalability, efficiency, and the theoretical foundations connecting compression, probabilistic modeling, and language understanding across diverse modalities and languages.

[1] Wayne Xin Zhao, Kun Zhou, Junyi Li, Tianyi Tang, Xiaolei Wang, Yupeng Hou, Yingqian Min, Beichen Zhang, Junjie Zhang, Zican Dong, et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223, 2023.

[2] Alec Radford. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training, 2018.

[3] Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, Ilya Sutskever, et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog, 1(8):9, 2019.

[4] Tom B Brown. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165, 2020.

[6] Abhimanyu Dubey, Abhinav Jauhri, Abhinav Pandey, Abhishek Kadian, Ahmad Al-Dahle, Aiesha Letman, Akhil Mathur, Alan Schelten, Amy Yang, Angela Fan, et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, 2024.

[7] Ashish Vaswani. Attention is all you need. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03762, 2017.

[8] Ronald A Fisher. On the mathematical foundations of theoretical statistics. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, containing papers of a mathematical or physical character, 222(594-604):309–368, 1922.

[9] Fan Bao, Shen Nie, Kaiwen Xue, Yue Cao, Chongxuan Li, Hang Su, and Jun Zhu. All are worth words: A vit backbone for diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 22669–22679, 2023.

[10] William Peebles and Saining Xie. Scalable diffusion models with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pages 4195–4205, 2023.

[11] Tim Brooks, Bill Peebles, Connor Holmes, Will DePue, Yufei Guo, Li Jing, David Schnurr, Joe Taylor, Troy Luhman, Eric Luhman, Clarence Ng, Ricky Wang, and Aditya Ramesh. Video generation models as world simulators. 2024. URL

https://openai.com/research/video-generation-models-as-world-simulators.

[12] Gregoire Deletang, Anian Ruoss, Paul-Ambroise Duquenne, Elliot Catt, Tim Genewein, Christopher Mattern, Jordi Grau-Moya, Li Kevin Wenliang, Matthew Aitchison, Laurent Orseau, et al. Language modeling is compression. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations.

[13] Yuzhen Huang, Jinghan Zhang, Zifei Shan, and Junxian He. Compression represents intelligence linearly. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.09937, 2024.

[14] Claude Elwood Shannon. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell system technical journal, 27(3):379–423, 1948.

[15] Lukas Berglund, Meg Tong, Max Kaufmann, Mikita Balesni, Asa Cooper Stickland, Tomasz Korbak, and Owain Evans. The reversal curse: Llms trained on" a is b" fail to learn" b is a". arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.12288, 2023.

[16] Jacob Austin, Daniel D Johnson, Jonathan Ho, Daniel Tarlow, and Rianne Van Den Berg. Structured denoising diffusion models in discrete state-spaces. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:17981–17993, 2021.

[17] Aaron Lou, Chenlin Meng, and Stefano Ermon. Discrete diffusion language modeling by estimating the ratios of the data distribution. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.16834, 2023.

[18] Jiaxin Shi, Kehang Han, Zhe Wang, Arnaud Doucet, and Michalis K Titsias. Simplified and generalized masked diffusion for discrete data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.04329, 2024.

[19] Subham Sekhar Sahoo, Marianne Arriola, Yair Schiff, Aaron Gokaslan, Edgar Marroquin, Justin T Chiu, Alexander Rush, and Volodymyr Kuleshov. Simple and effective masked diffusion language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.07524, 2024.

[20] Jingyang Ou, Shen Nie, Kaiwen Xue, Fengqi Zhu, Jiacheng Sun, Zhenguo Li, and Chongxuan Li. Your absorbing discrete diffusion secretly models the conditional distributions of clean data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.03736, 2024.

[21] Hugo Touvron, Louis Martin, Kevin Stone, Peter Albert, Amjad Almahairi, Yasmine Babaei, Nikolay Bashlykov, Soumya Batra, Prajjwal Bhargava, Shruti Bhosale, et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, 2023.

[22] Jacob Devlin. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

[23] Huiwen Chang, Han Zhang, Lu Jiang, Ce Liu, and William T Freeman. Maskgit: Masked generative image transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 11315–11325, 2022.

[24] Joshua Ainslie, James Lee-Thorp, Michiel de Jong, Yury Zemlyanskiy, Federico Lebron, and Sumit Sanghai. Gqa: Training generalized multi-query transformer models from multi-head checkpoints. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 4895–4901, 2023.

[25] An Yang, Baosong Yang, Binyuan Hui, Bo Zheng, Bowen Yu, Chang Zhou, Chengpeng Li, Chengyuan Li, Dayiheng Liu, Fei Huang, Guanting Dong, Haoran Wei, Huan Lin, Jialong Tang, Jialin Wang, Jian Yang, Jianhong Tu, Jianwei Zhang, Jianxin Ma, Jianxin Yang, Jin Xu, Jingren Zhou, Jinze Bai, Jinzheng He, Junyang Lin, Kai Dang, Keming Lu, Keqin Chen, Kexin Yang, Mei Li, Mingfeng Xue, Na Ni, Pei Zhang, Peng Wang, Ru Peng, Rui Men, Ruize Gao, Runji Lin, Shijie Wang, Shuai Bai, Sinan Tan, Tianhang Zhu, Tianhao Li, Tianyu Liu, Wenbin Ge, Xiaodong Deng, Xiaohuan Zhou, Xingzhang Ren, Xinyu Zhang, Xipin Wei, Xuancheng Ren, Xuejing Liu, Yang Fan, Yang Yao, Yichang Zhang, Yu Wan, Yunfei Chu, Yuqiong Liu, Zeyu Cui, Zhenru Zhang, Zhifang Guo, and Zhihao Fan. Qwen2 technical report, 2024. URL

https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.10671.