Toward Efficient Agents: A Survey of Memory, Tool learning, and Planning

Xiaofang Yang$^{1,2,\dagger}$, Lijun Li$^{1,\dagger,✉}$, Heng Zhou$^{1,3,\dagger}$, Tong Zhu$^{1,\dagger}$, Xiaoye Qu$^{1}$, Yuchen Fan$^{1,4}$, Qianshan Wei$^{5}$, Rui Ye$^{4}$, Li Kang$^{1,4}$, Yiran Qin$^{6}$, Zhiqiang Kou$^{7}$, Daizong Liu$^{8}$, Qi Li$^{5}$, Ning Ding$^{9}$, Siheng Chen$^{4}$, Jing Shao$^{1,✉}$

$^{1}$ Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Laboratory

$^{2}$ Fudan University

$^{3}$ University of Science and Technology of China

$^{4}$ Shanghai Jiaotong University

$^{5}$ Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences

$^{6}$ The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Shenzhen)

$^{7}$ Hong Kong Polytechnic University

$^{8}$ Wuhan University

$^{9}$ Tsinghua University

Abstract

Recent years have witnessed increasing interest in extending large language models into agentic systems. While the effectiveness of agents has continued to improve, efficiency, which is crucial for real-world deployment, has often been overlooked. This paper therefore investigates efficiency from three core components of agents: memory, tool learning, and planning, considering costs such as latency, tokens, steps, etc. Aimed at conducting comprehensive research addressing the efficiency of the agentic system itself, we review a broad range of recent approaches that differ in implementation yet frequently converge on shared high-level principles including but not limited to bounding context via compression and management, designing reinforcement learning rewards to minimize tool invocation, and employing controlled search mechanisms to enhance efficiency, which we discuss in detail. Accordingly, we characterize efficiency in two complementary ways: comparing effectiveness under a fixed cost budget, and comparing cost at a comparable level of effectiveness. This trade-off can also be viewed through the Pareto frontier between effectiveness and cost. From this perspective, we also examine efficiency oriented benchmarks by summarizing evaluation protocols for these components and consolidating commonly reported efficiency metrics from both benchmark and methodological studies. Moreover, we discuss the key challenges and future directions, with the goal of providing promising insights.

$^{\dagger}$ Main contributors

$^{✉}$ Corresponding Author

Keywords: Agents, Efficiency, Agent Memory, Tool Learning, Planning

Date: January 20th, 2026

Projects: https://efficient-agents.github.io/

Code Repository: https://github.com/yxf203/Awesome-Efficient-Agents

Contact: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]

1. Introduction

The landscape of Artificial Intelligence has undergone a paradigm shift, evolving from the era of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs), and the emergence of LLM-based Agents currently [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Unlike their predecessors, which primarily focused on perception or static text generation, agentic systems do not merely process information; they actively interact with external environments to execute complex, multi-step workflows across diverse domains, such as autonomous software engineering [7, 8] and accelerated scientific discovery [9, 10, 11].

However, this shift toward autonomous action has introduced a critical bottleneck: efficiency. While the deployment of LLMs is already resource-intensive, this challenge is significantly exacerbated in agentic systems. Unlike a standard LLM that typically operates in a linear, single-turn query-response format, an agent consumes exponentially more resources due to its recursive nature. To automate intricate real-world tasks [12, 13, 14, 8], agents must perform extensive memory management, iterative tool usage, and complex planning over multiple steps. This multi-step execution leads to prohibitive latency, context window saturation, and excessive token consumption, raising profound concerns regarding the long-term sustainability and equitable accessibility of these increasingly capable systems.

To understand the urgency of agent efficiency, one must examine the typical agentic workflow. Upon receiving a user instruction, an agent engages in a recursive loop that heavily uses the following key components: memory, planning, and tool learning to observe output and provide the final solution.

$ \begin{aligned} \mathrm{Input}\rightarrow \Bigl[, \underbrace{\mathrm{Memory}}{Context} \rightarrow \underbrace{\mathrm{Planning}}{Decision} \rightarrow \underbrace{\mathrm{Tool\ Learning}}{Action} \rightarrow \underbrace{\mathrm{Observation}}{Feedback} , \Bigr] _{!n} \rightarrow \mathrm{Solution}. \end{aligned} $

In each iteration $n$, the system must first retrieve relevant context from memory, reason over the current state to formulate a plan, execute a specific tool-incorporated action, and process the resulting observation. This cycle creates a compounding accumulation of tokens, where the output of step $n$ becomes the input cost of step $n+1$, resulting in high inference costs and slow response times. Consequently, mere model compression is insufficient. We therefore define an efficient agent as follows:

**Efficient agent** is not a smaller model, but as an agentic system optimized to maximize task success rates while minimizing resource consumption, including token usage, inference latency, and computational cost across memory, tool usage, and planning modules.

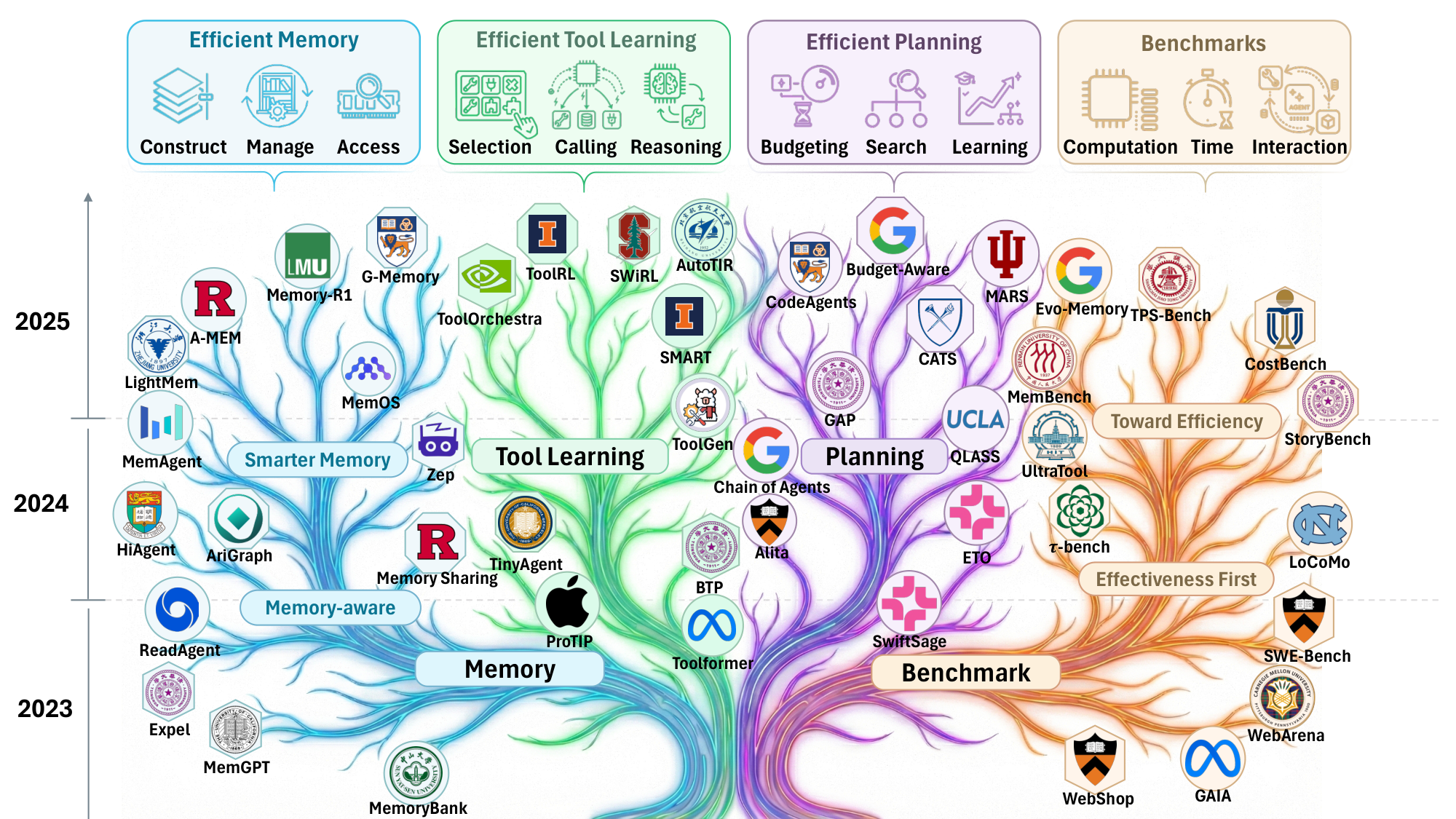

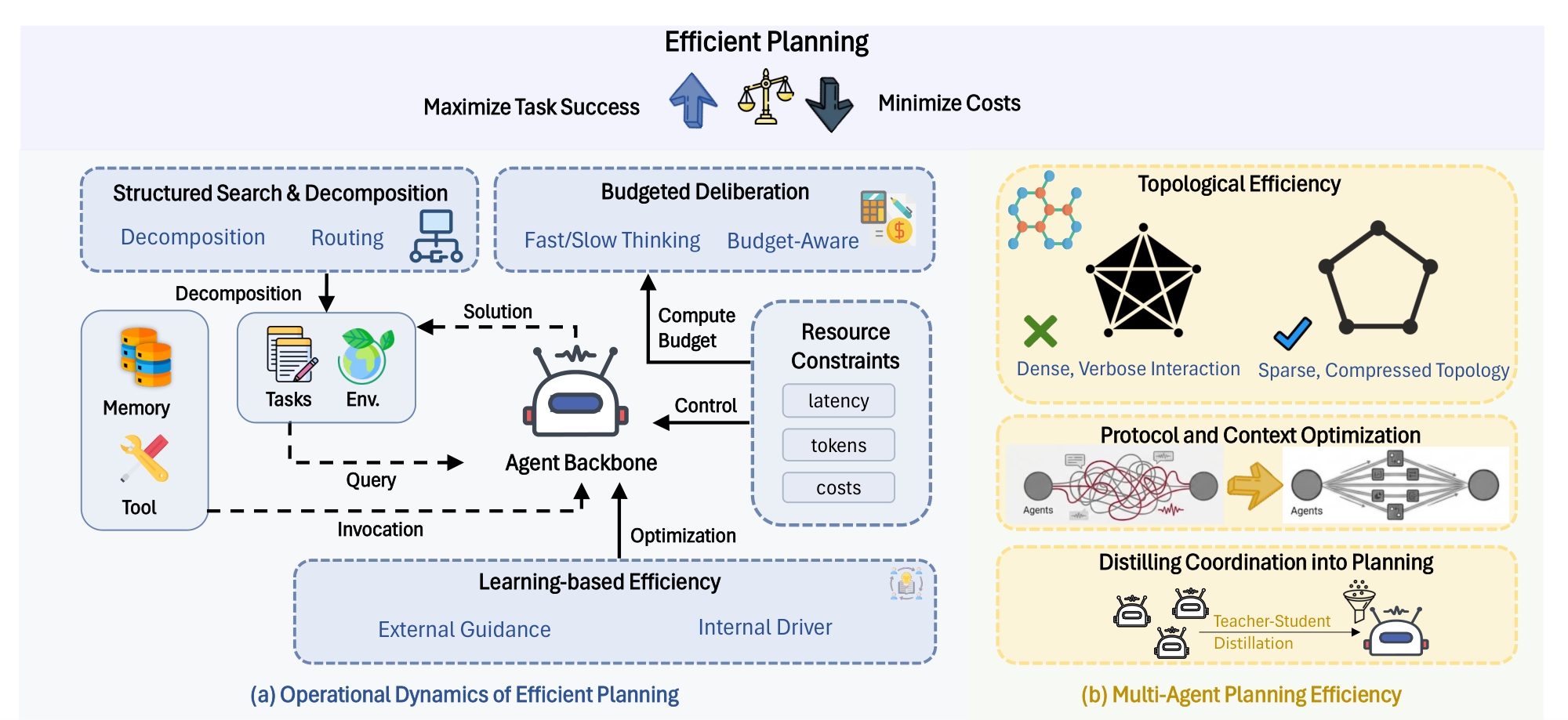

Our survey aims to systematize the numerous efforts in this emerging field. While a large number of existing surveys focus on Efficient LLMs [15, 16, 17], which serve as the backbone of agents, there is a lack of comprehensive literature addressing the efficiency of the agentic system itself. To bridge this gap, we categorize existing works into three strategic directions: 1) Efficient Memory: Techniques for compressing historical context, managing memory storage, and optimizing context retrieval. 2) Efficient Tool Learning: Strategies to minimize the number of tool calls and reduce the latency of external interactions. 3) Efficient Planning: Strategies to reduce the number of executing steps and API calls required to solve a problem.

The remainder of this survey is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the preliminaries and highlights the efficiency gap between agents and LLMs. Section 3 through Section 5 explore component-level efficiency, with a focus on memory, tool learning, and planning optimizations. Subsequently, Section 6 addresses the quantification of efficiency. The survey concludes with a discussion on open challenges and future research directions.

2. Preliminaries

2.1 Agent Formulation

We model an LLM-based agent interacting with an environment as a partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP) augmented with an external tool interface and an explicit memory component. Formally, we define the overall model as

$ \mathcal{M} = (\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{O}, \mathcal{A}, P, R, \gamma;\ \mathcal{T}, \Psi;\ \mathcal{M}_{mem}, U, \rho). $

Here $\mathcal{S}$ denotes the latent environment state space, $\mathcal{O}$ the observation space, and $\mathcal{A}$ the agent action space. The environment dynamics are given by the transition kernel $P$, the reward function $R$, and the discount factor $\gamma\in[0, 1)$.

The agent is additionally equipped with a set of external tools $\mathcal{T}$ and a tool interface $\Psi$, which specifies how tool calls are executed and what tool outputs are returned to the agent. Finally, we model explicit agent memory with memory state space $\mathcal{M}_{mem}$, an update rule $U$ that maps the current memory and available information to the next memory state, and an initialization distribution $\rho$ over the initial memory.

2.2 From Pure LLMs to Agents

We define efficiency through a cost–performance trade-off: achieving comparable performance with lower cost, or achieving higher performance under a similar cost budget.

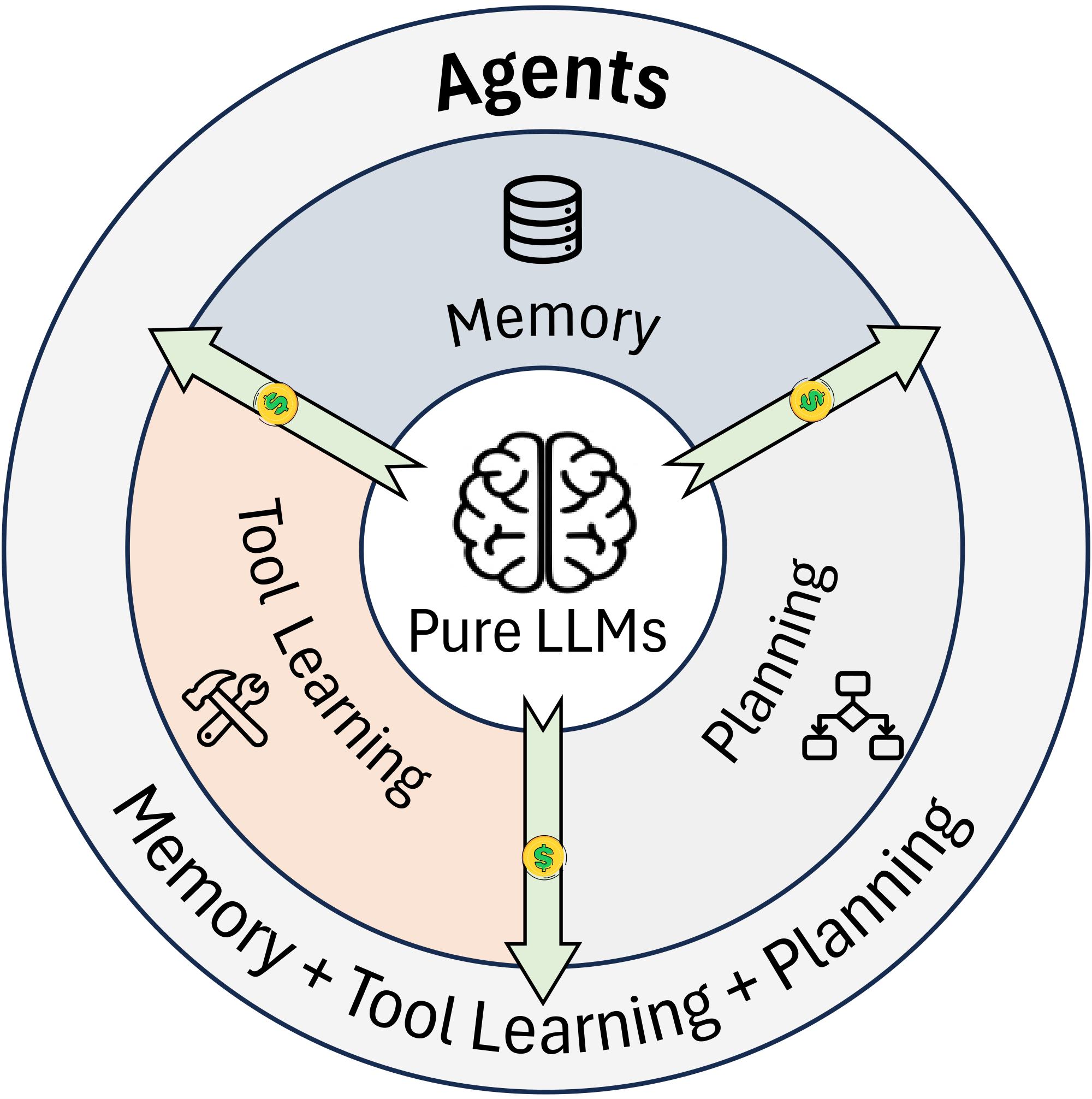

We acknowledge that many efficiency techniques used in LLM-based agents overlap with those for standalone LLMs (e.g., model compression and inference acceleration). In agents, however, these techniques mainly serve as foundational enablers rather than addressing the agent-specific sources of inefficiency. As summarized by [18], compared to pure LLMs, LLM-based agents exhibit more human-like decision-making by augmenting a base model with cognitive components such as planning and memory.

Accordingly, in this subsection we focus on what differentiates agent efficiency from LLM efficiency. From a functional perspective, an agent is characterized by its ability to (i) plan and act over multiple steps, (ii) invoke external tools or environment commands to acquire information and execute operations, and (iii) condition subsequent decisions on retrieved or updated memory.

As illustrated in Figure 2, agentic systems introduce additional cost sources beyond generation. For a pure LLM, the inference cost is often dominated by token generation and can be approximated as:

$ \mathrm{Cost}{LLM} \approx \alpha, N{tok}, $

where $N_{\text{tok}}$ is the number of generated reasoning tokens and $\alpha$ captures the per-token cost (e.g., time or monetary cost). In contrast, an agent may incur additional overhead from tools, memory, and retries as needed:

$ \mathrm{Cost}{agent} \approx \alpha, N{tok}

- \mathbb{I}{tool}\cdot \mathrm{Cost}{tool}

- \mathbb{I}{mem}\cdot \mathrm{Cost}{mem}

- \mathbb{I}{retry}\cdot \mathrm{Cost}{retry}, $

where $\mathbb{I}{\text{tool}}, \mathbb{I}{\text{mem}}, \mathbb{I}_{\text{retry}} \in {0, 1}$ are indicator variables that equal $1$ if the agent invokes tools, accesses memory, or performs retries, respectively, and $0$ otherwise. Therefore, improving agent efficiency is not only about reducing language generation, but also about reducing the frequency and improving the selectivity of tool or memory invocations and retries along a trajectory, to achieve a better cost–performance trade-off.

3. Efficient Memory

A major efficiency bottleneck for LLM agents is the computational and token overhead induced by long contexts and long-horizon interactions, where agents may repeatedly reprocess large histories to act. Memory-augmented reasoning provides a principled way to alleviate this inefficiency. By storing and reusing past experience, including successes, failures, and interaction traces, agents can avoid redundant computation, make more informed decisions, and reduce costly retries. In this sense, memory is not merely an auxiliary component. It is a key mechanism for improving the overall efficiency-effectiveness trade-off of agent systems.

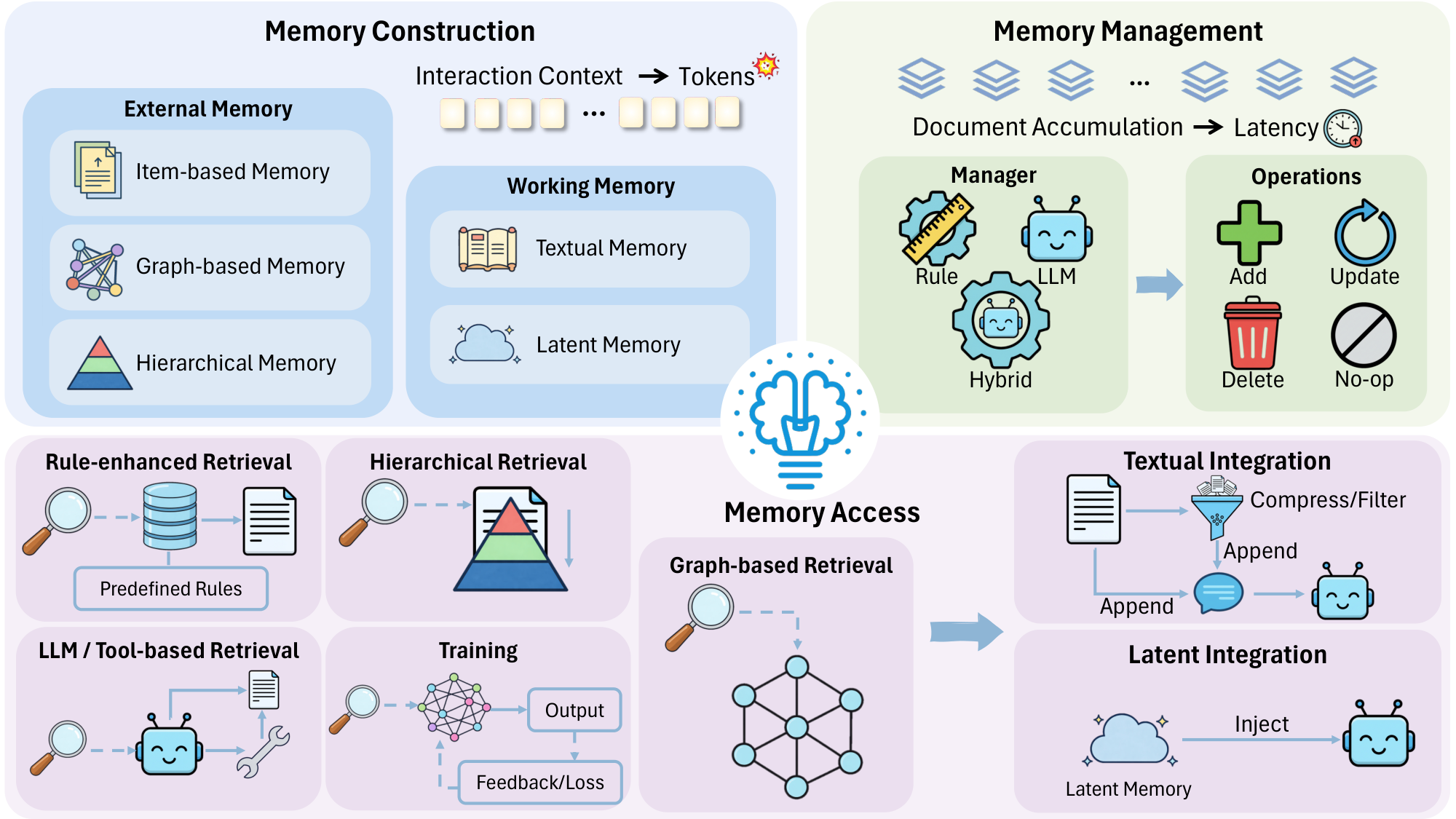

We organize this section around the lifecycle of agent memory, covering memory construction, memory management, and memory access. Because memory is central to efficiency gains, how to design an efficient memory module becomes an important problem. We therefore discuss efficiency-oriented designs throughout this lifecycle, focusing on how to maximize the benefit of memory while minimizing additional overhead. Figure 3 provides a structured overview of our taxonomy, and Table 1 lists representative works for an at-a-glance summary.

\begin{tabular}{l|l|l|l}

\toprule

\textbf{Method} & \textbf{Category} & \textbf{Core Mechanism} & \textbf{Resource Link} \\

\midrule

\multicolumn{4}{c}{\textbf{\textit{Working Memory}}}\\

\midrule

COMEDY ([19]) & Textual & Two-stage memory distillation & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/nuochenpku/COMEDY)\\

MemAgent ([20]) & Textual & Overwrite fixed memory & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/BytedTsinghua-SIA/MemAgent)\\

MEM1 ([21]) & Textual & Update a compact shared internal state & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/MIT-MI/MEM1)\\

AgentFold ([22]) & Textual & Proactive context folding & N/A \\

DC ([23]) & Textual & Persistent, evolving memory & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/suzgunmirac/dynamic-cheatsheet)\\

Activation Beacon ([24]) & Latent & Activation-level beacon for long context & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/FlagOpen/FlagEmbedding/)\\

MemoRAG ([25]) & Latent & KV-compressed global memory representation & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/qhjqhj00/MemoRAG)\\

MemoryLLM ([26]) & Latent & a fixed-size latent memory pool & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/wangyu-ustc/MemoryLLM)\\

M+ ([27]) & Latent & Dual-level latent memory; co-trained retriever & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/wangyu-ustc/MemoryLLM)\\

Memory$^3$ ([28]) & Latent & Externalize knowledge into retrievable sparse KV memories & N/A \\

Titans ([29]) & Latent & Sliding-window attention; test-time trainable neural long-term memory & N/A \\

MemGen ([30]) & Latent & On-demand latent memory synthesis & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/KANABOON1/MemGen)\\

\midrule

\multicolumn{4}{c}{\textbf{\textit{External Memory}}}\\

\midrule

MemoryBank ([31]) & Item-based & Ebbinghaus forgetting curve–based memory management & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/zhongwanjun/MemoryBank-SiliconFriend)\\

RECOMP ([32]) & Item-based & Compress retrieved documents & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/carriex/recomp)\\

Expel ([33]) & Item-based & experiential learning; insight distillation and management & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/LeapLabTHU/ExpeL)\\

Human-like memory ([34]) & Item-based & Cue-triggered memory recall & N/A \\

SeCom ([35]) & Item-based & Segment-level memory; compression-based denoising for retrieval & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/microsoft/SeCom)\\

Memory-R1 ([36]) & Item-based & Adaptive memory CRUD and memory distillation, via two RL-trained agents & N/A \\

Mem0 ([37]) & Item-based & Extract candidate memories; memory CRUD & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/mem0ai/mem0)\\

agentic plan caching ([38]) & Item-based & Store plan template; plan cache lookup (hit/miss) and update & N/A \\

LD-Agent ([39]) & Item-based & Separate different memory; topic-based retrieval & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/leolee99/LD-Agent)\\

MemoChat ([40]) & Item-based & Structured on-the-fly memos & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/LuJunru/MemoChat)\\

RMM ([41]) & Item-based & Topic-based memory organization; consolidation (add/merge); online RL reranker & N/A \\

Memento ([42]) & Item-based & Parametric case retrieval via an online-updated Q-function & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/Agent-on-the-Fly/Memento)\\

MemInsight ([43]) & Item-based & Attribute-augmented memory; attribute-guided retrieval & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/amazon-science/MemInsight)\\

ReasoningBank ([44]) & Item-based & Distill strategies from failures and successes to cut exploration steps & N/A \\

A-MEM ([45]) & Item-based & Atomic structured notes; link generation and memory evolution & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/agiresearch/A-mem)\\

ACE ([46]) & Item-based & Incremental delta updates, lightweight merge and de-dup & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/ace-agent/ace)\\

Agent KB ([47]) & Item-based & Cross-framework reusable experience Knowledge Base & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/OPPO-PersonalAI/Agent-KB)\\

GraphReader ([48]) & Graph-based & Graph-guided coarse-to-fine exploration & N/A \\

KG-Agent ([49]) & Graph-based & Tool-based hop-local KG processing & N/A \\

Zep ([50]) & Graph-based & Temporal KG memory & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/getzep/zep)\\

Mem0$^g$ ([37]) & Graph-based & Extract candidate nodes; graph updation & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/mem0ai/mem0)\\

AriGraph ([51]) & Graph-based & Memory graph; semantic-to-episodic cascading retrieval & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/AIRI-Institute/AriGraph)\\

D-SMART ([52]) & Graph-based & Structured OWL-compliant KG & N/A \\

MemGPT ([53]) & Hierarchical & OS-style virtual memory paging for context & \faIcon{globe}\, [Website](https://research.memgpt.ai)\\

MemoryOS ([54]) & Hierarchical & OS-inspired three-tier memory hierarchy with policy-based inter-tier updates & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/BAI-LAB/MemoryOS)\\

MemOS ([55]) & Hierarchical & Policy-guided type transformation of MemCubes across three memory forms & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/MemTensor/MemOS)\\

ReadAgent ([56]) & Hierarchical & Gist memory compression; on-demand lookup & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/read-agent/read-agent.github.io/blob/main/assets/read_agent_demo.ipynb)\\

HiAgent ([57]) & Hierarchical & Subgoals as memory chunks; on-demand trajectory retrieval & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/HiAgent2024/HiAgent)\\

H-MEM ([58]) & Hierarchical & Layer-by-layer retrieval & N/A \\

LightMem ([59]) & Hierarchical & Pre-compression; soft update (test-time); sleep-time update (offline) & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/zjunlp/LightMem)\\

\midrule

\multicolumn{4}{c}{\textbf{\textit{Multi-Agent Memory}}}\\

\midrule

MS ([60]) & Shared & Shared memory pool; selective addition; continual retriever training & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/GHupppp/InteractiveMemorySharingLLM)\\

G-Memory ([61]) & Shared & three-tier graph memory with bi-directional coarse-to-fine retrieval & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/bingreeky/GMemory)\\

RCR-Router ([62]) & Shared & Feedback-refined iterative router under a token budget & N/A \\

MemIndex ([63]) & Shared & Intent-indexed bipartite graphs; semantic slicing and dynamic indexing & N/A \\

MIRIX ([64]) & Shared & Six-module hierarchical memory with staged retrieval and parallel updates & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/Mirix-AI/MIRIX)\\

Intrinsic Memory Agents ([65]) & Local & Role-aligned templates; intrinsic iterative updates & N/A \\

AgentNet ([66]) & Local & Fixed-size memory modules for routing/execution; dynamic pruning & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/zoe-yyx/AgentNet)\\

DAMCS ([67]) & Local & Decentralized per-agent STWM/LTM with goal-oriented hierarchical knowledge graph & \faIcon{globe}\, [Website](https://happyeureka.github.io/damcs/)\\

SRMT ([68]) & Mixed & Personal latent memory and globally broadcast shared recurrent memory & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/Aloriosa/srmt)\\

Collaborative Memory ([69]) & Mixed & Policy-based filtering/transformation of memory fragments; shared-memory reuse & N/A \\

LEGOMem ([70]) & Mixed & Role-aware memory routing; runtime-efficient retrieval scheduling & N/A \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

3.1 Memory Construction

No matter whether we target long-context tasks or long-term interactions, the core challenge is handling extensive context or interaction history. Naively appending raw history into the prompt is often impractical: token usage grows rapidly, and performance can even degrade when relevant information is buried in long sequences, as observed in the “lost in the middle” phenomenon ([71]). In addition, an LLM's context window is finite, whereas the amount of potentially relevant information is effectively unbounded. These constraints motivate memory construction, which compresses and organizes past information into more manageable representations. Many existing works build memory through summarization, reducing token consumption and improving efficiency.

3.1.1 Working Memory

Working memory is the information directly available at inference time that conditions generation. Here, the term is broader than the common definition that limits working memory to context tokens. It includes the text currently present in the prompt or context window, and latent memory in the form of continuous signals that influence the forward computation without being represented as tokens, such as soft prompts, KV cache, and hidden states. Latent memory can arise inside the model or be stored externally and injected as continuous conditioning. Embeddings count as latent memory only when they are provided to the model as such conditioning signals; embeddings used only to support retrieval are treated separately in Section 3.1.2.

Textual Memory.

In LLM-based agents, textual memory is a common instantiation of working memory. To address the long-context challenge, many methods aim to keep the working memory in the prompt at a roughly constant size. In practice, this is often achieved by frequently rewriting or compressing the memory as the process evolves.

COMEDY ([19]) uses an LLM to generate and compress memory: it extracts session-specific memories from past conversations and then condenses them into a compact representation of key events, the user profile, and relationship changes. MemAgent ([20]) and MEM1 ([21]) both process long inputs sequentially by rewriting and updating a compact memory state at each step: MemAgent updates a summarized memory after each chunk, while MEM1 uses reinforcement learning [72] to maintain a fixed-length internal state tagged by

By retaining a compact memory in the prompt rather than the full history, these methods reduce the effective context length the LLM needs to attend to, thereby improving long-context performance while decreasing computational cost and increasing efficiency.

Latent Memory.

Besides textual working memory, recent work also lets an agent keep its state in latent form, such as hidden activations or KV caches. This kind of memory is not shown as text, but it can be read and updated by the model. In many cases it is much cheaper than storing and re-reading the full interaction history, and thus is attractive for efficient agents.

One group of methods builds compact latent memory by compressing long contexts into a small set of activations in KV space. Activation Beacon ([24]) partitions the context into chunks and fine-grained units, interleaves beacon tokens by a compression ratio, and uses progressive compression to distill layer-wise KV activations into the beacons, which are accumulated as latent memory while raw-token activations are discarded. MemoRAG ([25]) performs memory formation by inserting memory tokens after each window as information carriers of global memory in KV space, and updating a memory-token KV cache across windows with separate weight matrices; the compact global memory can later be reused (e.g., as retrieval clues).

A second group maintains an external pool of latent memory and integrates it into the backbone LLM via attention at inference time, enabling reuse of stored information across steps and episodes. MemoryLLM ([26]) maintains a fixed-size memory pool of memory tokens updated via self-update, enabling reuse of stored latent knowledge without lengthening the prompt. M+ ([27]) adds a GPU/CPU two-tier long-term memory with a co-trained retriever that fetches only a few relevant memory tokens per layer, and Memory$^3$ ([28]) encodes a KB as sparse explicit key–value memory injected into attention at decoding time to avoid repeated document reading.

A third group lets latent memory be a separate neural module that can learn online together with the agent. Titans ([29]) builds latent memory by updating a neural memory module at test time, writing only when prediction error is high and skipping updates otherwise. MemGen ([30]) constructs latent memories via an RL-trained memory trigger and a memory weaver that produces compact latent memory tokens as the stored representation.

Strictly speaking, some of the methods above are proposed as general memory modules for LLMs rather than full agent frameworks. However, from the view of efficient agent memory, they play the same role: they compress long interaction histories into compact latent states, update these states only when needed, and expose them to the policy through attention or simple interfaces. This allows an agent to keep and reuse long-horizon information without replaying the entire textual trajectory at each step.

- **Advantages**: The working memory is directly conditioned upon during generation, eliminating the latency and overhead associated with external retrieval or repeated encoding.

- **Disadvantages**: Expanding the working set leads to computational growth for textual memory or increased memory footprint for latent states, and risks performance degradation due to information dilution in long contexts.

- **Applicable Scenarios**: Textual memory is best for logic-heavy tasks within moderate context limits, while latent memory suits efficiency-critical applications requiring the reuse of historical states without re-processing.

3.1.2 External Memory

External memory refers to information stored outside the model in token-level form, including document collections, knowledge graphs, and retrieval systems such as RAG. It does not condition generation directly. Instead, it is accessed through retrieval and then expressed as tokens placed into the prompt or context window.

Item-based Memory.

Early agent-memory systems often store full trajectories or experiences, sometimes alongside summaries, which leads to long context and inefficiency. MemoryBank ([31]) stores daily conversation records and summarizes past events and user profiles from these conversations, but it incurs high token costs. Similarly, Expel ([33]) suffers from a similar limitation, as it accumulates experiences through trial and error and distills them into natural-language insights.

To be more efficient, some works adopt methods such as memory extraction, compress or summarization to directly reduce context length. This way thereby lowers input token consumption while yielding a shorter but more informative context.

Human-like memory ([34]) extracts episodic memories from users dialogues, encapsulating content and temporal context into database structure. SeCom ([35]) uses segmentation model to divide long-term conversations into topic-coherent segmentation, and applies the compress model to denoise the segmentation, which further promotes efficient retrieval.

Memory-R1 ([36]) and Mem0 ([37]) both extract and summarize ongoing dialogue into candidate memories for downstream updating; Memory-R1 does so at each turn, while Mem0 forms candidate memories from the new message pair, using a conversation summary and recent messages as context. Agentic plan caching ([38]) turns a successful run into a reusable cache entry by rule-based filtering the execution log and then using a lightweight LLM to remove context-specific details, storing the result as a (keyword, plan template) pair. LD-Agent ([39]) separates event and persona memory, using short-term and long-term banks for timestamped dialogue context and embedded event summaries, and a persona extractor to store user and agent traits in long-term persona banks.

Beyond the extraction and compression strategies discussed above, another way to improve efficiency is to design more structured memory systems. Organizing memory more systematically can enable faster retrieval, better utilization of stored information, and improved overall performance. And one type of the structured memory system is topic-indexed memories, which organizes interactions into topic-level groups and stores each topic summary together with its corresponding dialogue segment for efficient retrieval. MemoChat ([40]) and RMM ([41]) both build topic-indexed memories. MemoChat records topic–summary–dialogue entries on the fly, while RMM groups each session by topic and stores each topic summary with its corresponding dialogue segment. Then, some system constructs the attribute-annotated memory items by enriching each interaction with structured attributes such as LLM-mined attribute value pairs, contextual descriptions, keywords, and tags to support fine-grained retrieval. MemInsight ([43]) and A-MEM ([45]) both enrich raw interactions with structured attributes for retrieval: MemInsight annotates memories with LLM-mined attribute–value pairs, while A-MEM converts each interaction into an atomic note with LLM-generated contextual descriptions, keywords, and tags. Besides, a typical way is to distill experience libraries for reusable decision by summarizing trajectories or execution logs into standardized experience entries that capture reusable strategies, domain concepts, and common failure modes for retrieval and reuse. ReasoningBank ([44]) summarizes successful and failed trajectories into structured memory items with a title, brief description, and content, and stores them with the task query and trajectory for embedding-based retrieval. ACE ([46]) represents context as structured, itemized bullets, each with a unique identifier, counters tracking how often it was marked helpful or harmful, and content such as a reusable strategy, domain concept, or common failure mode. Agent KB ([47]) turns execution logs into structured experience entries through human-guided abstraction, using few-shot prompting and a standardized cross-framework action vocabulary.

Graph-based Memory.

It's obvious that graph-based memory is also a structured memory form. Some methods focus on constructing graph-structured representations from long inputs or KG interactions, so multi-hop evidence can be organized and accessed efficiently.

Targeted at the long context task, GraphReader ([48]) segments long text into chunks, compresses them into key elements and atomic facts, and uses these to construct a graph that captures long-range dependencies and multi-hop relations. KG-Agent ([49]) constructs a task-specific subgraph by tool calls and records the retrieved entities and relations as knowledge memory.

Another line of work constructs long-term memory directly as a dynamic knowledge graph, turning interactions into entities, relations, and time-aware facts that can be incrementally updated.

Zep ([50]) builds memory as a temporally-aware knowledge graph by ingesting time-stamped episodes, extracting/aligning entities and relations, storing fact edges with periods of validity and additionally constructs a community subgraph that clusters strongly connected entities and stores high-level community summaries. Mem0$^g$ ([37]) represents memory as a directed labeled graph, where an LLM converts new messages into entities and relation triplets that form candidate nodes or edges for graph updates. D-SMART ([52]) incrementally constructs an OWL-compliant dialogue KG by first distilling each turn into an assertion-like statement, then converting it into a KG fragment for integration. AriGraph ([51]) updates a unified semantic–episodic memory graph online by adding an episodic node for each observation and extracting triplets to update the semantic graph, linking the two via episodic edges.

Graph-based memory represents entities and their relations as a structured graph. Building the graph already compresses and normalizes the history by merging repeated content about the same entity into a single node and keeping only relevant relations as edges. This makes construction more efficient by producing a compact structure that avoids unbounded prompt growth and supports fast retrieval later.

Hierarchical Memory.

Hierarchical memory organizes information into multiple linked levels, enabling coarse-to-fine, on-demand access. Most hierarchical memory methods consider both structure and content, but with different emphases. Accordingly, related work can be grouped by whether it places more weight on structural organization and management or on content abstraction and indexing.

System-oriented hierarchical memory designs define explicit storage tiers and read/write interfaces to manage long interaction history. MemGPT ([53]) constructs a hierarchical memory by partitioning the in-context prompt into system instructions, a writable working context, and a FIFO message buffer, and storing the remaining history and documents in external recall and archival memory. MemoryOS ([54]) adopts an OS-inspired hierarchical memory design with three storage tiers: short-term memory stores recent dialogue pages, mid-term memory groups pages into topic segments with summaries, and long-term personal memory maintains user and agent persona information. MemOS ([55]) standardizes memory as MemCubes, each composed of a structured metadata header and a memory payload that can encapsulate plaintext, activation states, or parameter deltas. New interactions are incrementally turned into MemCubes and organized in a hierarchical structure.

Content-oriented approaches build hierarchical indices by segmenting and compressing documents or trajectories into multi-granularity summaries. ReadAgent ([56]) splits a long document into pages and summarizes each page into a page-linked gist memory, forming a simple hierarchical index. HiAgent ([57]) compresses working memory into subgoals and observations, and stores full trajectories in external memory indexed by these summaries. H-MEM ([58]) constructs a hierarchical structure, with four memory layers: Domain Layer, Category Layer, Memory Trace Layer, and Episode Layer. It designs prompts to guide model to parse the interactions into these layers, which forms a progressively optimized index. LightMem ([59]) uses a sensory–STM–LTM pipeline that first pre-compresses inputs by the sensory module, then groups turns into topic segments for STM and periodically summarizes these segments into compact LTM entries.

- **Advantages**: Effectively unbounded long-term storage outside the model, reducing context overflow via targeted retrieval.

- **Disadvantages**: Adds system overhead and retrieval latency, with potential retrieval noise.

- **Applicable scenarios**: Item-based memory suits general long-trajectory agents, graph-based memory suits entity–relation and multi-hop reasoning tasks, while hierarchical memory suits ultra-long histories or large corpora needing coarse-to-fine retrieval.

3.2 Memory Management

Some methods, like Human-like memory ([34]), continually insert new memories into memory module, without any operation like updating, removing or merging, leading to memory space explosion. Therefore, the speed of the memory retrieval or recall will significantly decrease, which indicates that memory management is a highly important part for efficiency.

3.2.1 Rule-based Management

Rule-based management refers to predefined rules for updating, removing, and merging existing memories. Because these rules are static, this approach is inexpensive and prevents the overall memory size from growing uncontrollably.

MemoryBank ([31]) introduces an Ebbinghaus-inspired memory update rule that decays memories over time while reinforcing important ones. Building on this idea, H-MEM ([58]) retains forgetting-curve-based decay and further adds feedback-driven regulation to dynamically adjust memory according to user feedback. Experimental results in A-MEM ([45]) suggest that forgetting-curve-based memory management effectively controls memory size and reduces retrieval time. However, it also leads to a substantial drop in task performance.

Apart from forgetting-curve-based policies, a common rule-based strategy is trigger-driven memory maintenance, such as evicting or migrating items when a fixed-size buffer reaches capacity (e.g., FIFO replacement) ([53, 54]). In practice, these simple rules are often intertwined with LLM-based management, where the model summarizes or saves key information before items are removed or moved; more details are discussed in Section 3.2.3.

- **Advantages**: Fast, predictable, and low-cost memory management without extra LLM calls.

- **Disadvantages**: Static and task-agnostic rules can blindly prune or decay memory, causing critical information loss and hurting accuracy when retention matters.

3.2.2 LLM-based Management

LLM-based memory management can be broadly categorized by its decision form: selecting from a discrete set of operations versus generating open-ended updates.

A common formulation is operation selection, where the model picks an action from a predefined set (e.g., ADD/DELETE) and applies it to retrieved memories. Both Memory-R1 ([36]) and Mem0 ([37]) update an external memory by retrieving similar entries and choosing among ADD, UPDATE, DELETE, NOOP. Memory-R1 learns the choice via reinforcement learning, while Mem0 lets an LLM select the operation after vector-based retrieval. RMM ([41]) follows the same retrieve-then-update pattern: for each newly extracted topic memory, it retrieves the top- $k$ most similar entries from the memory bank and prompts an LLM to decide whether to merge or add. Separately, ExpeL ([33]) maintains an insights list through direct list editing, applying operations such as ADD, EDIT, UPVOTE, and DOWNVOTE to correct or gradually suppress erroneous and outdated insights.

A different formulation casts memory management as open-ended generation, where the model produces the update itself and implicitly performs the update operation rather than picking from a fixed action set. A-MEM ([45]) uses generative updates: it retrieves top- $k$ similar notes with a fixed encoder, then an LLM creates links and rewrites related notes via memory evolution.

- **Advantages**: Adaptive, task-aware decisions that keep the most relevant information while enabling effective compression or merging for a concise context.

- **Disadvantages**: Requires extra LLM calls during management, increasing compute cost and latency.

3.2.3 Hybrid Management

Hybrid memory management typically combines lightweight rule-based control with selective LLM-based operations to balance efficiency and effectiveness.

Typical designs include tier-specific management, where rule-based triggers promote or consolidate information across tiers and costly LLM updates are invoked only when necessary. MemoryOS ([54]) and LightMem ([59]) both adopt tier-specific, trigger-driven updates for hierarchical memory. MemoryOS manages STM as FIFO pages with overflow migrated to MTM, uses segment Heat scores in MTM for eviction and promotion, and updates LPM via an LLM, whereas LightMem triggers topic segmentation when the sensory buffer is full, summarizes topics into LTM when STM exceeds a token budget, and combines online soft updates with offline sleep-time consolidation. LD-Agent ([39]) uses a time-gap threshold as the trigger, summarizing the short-term cache into a long-term event record and clearing the cache to mark session boundaries. MemGPT ([53]) uses a hierarchical memory with main context and external context. A Queue Manager enforces token limits via memory pressure warnings, eviction, and recursive summarization, while a Function Executor turns model outputs into function calls to read and write across tiers.

Another management is item-level selection and pruning, using rules or heuristics for fast de-duplication and removal while relying on LLMs for semantic keep-or-drop decisions. Agent KB ([47]) and ACE ([46]) exemplify item-level selection and pruning for hybrid memory management. Agent KB reduces redundancy by thresholding embedding similarity and using an LLM ranker to keep the better experience, then evicts low-utility entries based on a learned utility score. ACE maintains a bulletized context through incremental delta updates and applies embedding-based grow-and-refine to merge, prune, and de-duplicate bullets, keeping the context compact.

Besides, some management also considers lifecycle policies that use lightweight metrics to schedule costly maintenance beyond tier transfer, such as consolidation, deduplication, and archiving. MemOS ([55]) manages MemCubes with explicit lifecycle and version tracking, using policy- and metric-driven modules such as MemScheduler and MemVault for deduplication, conflict handling, and archiving. Crucially, it supports type-aware transformation across Plaintext Memory, Activation Memory, and Parameter Memory, including promotion and demotion between types.

For graph-structured memory, hybrid management applies rule-based graph updates, while using LLMs to retrieve relevant subgraphs and verify contradictions or outdated content before updating relations. Zep ([50]), Mem0$^{g}$ ([37]), and AriGraph ([51]) follow a similar pattern for graph memory maintenance: an LLM judges semantic conflicts or staleness against retrieved related edges, while the graph is updated through rule-based operations such as edge invalidation or removal and insertion of new relations to preserve temporal or world-model consistency. Additionally, D-SMART ([52]) maintains an OWL-compliant Dynamic Structured Memory and performs two-stage conflict resolution by letting an LLM identify contradicted or superseded triples, pruning them before merging the new fragment, with an optional OWL reasoner for logical consistency checking.

- **Advantages**: Balances low-cost, predictable rule control with task-aware LLM decisions, invoking the LLM only when needed to keep memory both efficient and relevant.

- **Disadvantages**: Increases system complexity across tiers, and can suffer from suboptimal policy interactions, while LLM calls still add cost and latency when invoked.

3.3 Memory Access

Memory access retrieves and uses only the small subset of a large memory bank that matters for a query, balancing retrieval latency and token cost against downstream generation quality.

3.3.1 Memory Selection

Memory selection determines what to retrieve and how to retrieve it. Most methods follow vanilla retrieval, i.e., encoding the query and its context into embeddings and selecting relevant information via similarity search, while others employ improved retrieval mechanisms to enhance retrieval quality and efficiency.

Rule-enhanced Retrieval.

Some methods enhance retrieval by incorporating additional rule-based scoring factors and applying preprocessing steps before retrieval. Generative Agents ([73]) and Human-like memory ([34]) take time into consideration, namely recency and elapsed time in these works. Apart from this, Generative Agents adds importance, a score generated by LLM based on the semantic importance, and Human-like memory adds recall frequency, computed according to the mathematical model. Agent KB ([47]) employs a hybrid retrieval strategy that integrates lexical matching with semantic ranking by task similarity, combining both signals into a unified retrieval score. For long-term event retrieval, LD-Agent ([39]) combines semantic relevance, noun-based topic overlap, and an exponential time-decay factor into an overall score, and only retrieves memories whose semantic similarity exceeds a threshold.

While the aforementioned methods improve retrieval by adding additional scoring factors while keeping the computational cost comparable to vanilla retrieval, MemInsight ([43]) augments memories with LLM generated attribute value annotations and leverages these augmentations for retrieval, either by filtering memories via attribute matching or by embedding the aggregated augmentations for vector similarity search.

Graph-based Retrieval.

For graph-based memory, retrieval naturally follows the graph structure, enabling efficient neighbor expansion and more precise localization of relevant facts, especially when queries target entity- and relation-centric information. Given a textual query, Both AriGraph ([51]) and Mem0$^g$ ([37]) retrieve from a memory graph by anchoring on query-relevant facts and expanding neighbors into a local subgraph. AriGraph retrieves semantic triplets and then ranks episodic vertices via episodic search, whereas Mem0$^g$ pairs entity-centric subgraph construction with semantic triplet retrieval over relationship triplets.

LLM or Tool-based Retrieval.

Furthermore, there are methods that do not depend on a retriever, but instead leverage LLMs or external tools for obtaining relevant information.

For LLM-based retrieval, MemGPT ([53]) uses hierarchical memory without a fixed retrieval pipeline: memory tiers are exposed as tools, and the LLM selects the tier and operation under token budgets enforced by the system. MemoChat ([40]) exploits its memo structure by retrieving only the topic and summary, rather than the full topic–summary–dialogue, to reduce input length. ReadAgent ([56]) similarly delegates page lookup to the LLM, which decides when and which page(s) to consult.

However, while using a strong LLM can improve retrieval accuracy, it often incurs substantial overhead in both token consumption and inference latency, making it more suitable for low-frequency, high-stakes queries where correctness outweighs cost.

Besides, some methods rely on tool use for retrieval. GraphReader ([48]) predefines various tools, and employs the tools to read the memory step by step, from coarse-grained to fine-grained. D-SMART ([52]) lets the LLM select graph-operations such as Expand Entity and Find Path to retrieve n-hop neighbors from the global DSM and incrementally grow a task-specific subgraph, which serves as grounded context for answering.

Hierarchical Retrieval.

In line with the hierarchical memory structure, retrieval can likewise be organized hierarchically. Some retrieval methods can be considered as a simple way of hierarchical retrieval, such as the conceptually two-layer design. HiAgent ([57]) can recall the trajectories by a retrieval module, when the agent needs to obtain the details of the previous subgoal. Beyond such a two-layer setup, hierarchical retrieval can be made explicit through multi-layer indexing. In H-MEM ([58]), each memory embedding points to relevant sub-memories in the next layer, recursively indexing down to the last layer to retrieve relevant information, thereby accelerating retrieval. At a more system level, MemoryOS ([54]) uses tier-specific retrieval: STM returns the most recent dialogue pages, MTM retrieves top- $m$ candidate segments and selects top- $k$ relevant pages within them, and LPM performs semantic search over long-term user and agent memories.

Training.

As the memory bank grows, a fixed retriever can drift from what is truly useful, so recent work trains adaptive retrieval that prioritizes high-utility memories for better relevance and efficiency. RMM ([41]) adds a learnable reranker over a dense retriever and updates it online via RL using binary useful memory signals from Retrospective Reflection. Memento ([42]) learns a parametric Q-function over state–case pairs to rank and select Top-K cases, favoring historically high-reward cases over nearest neighbors.

- **Applicable scenarios**: Rule-enhanced retrieval fits settings with clear heuristics or constraints and tight budgets; graph-based retrieval fits entity–relation queries and multi-hop evidence chaining; LLM/tool-based retrieval fits low-frequency, high-stakes queries where correctness outweighs latency; hierarchical retrieval fits very large memory banks requiring coarse-to-fine lookup; training-based retrieval fits long-running systems where the memory distribution drifts over time.

3.3.2 Memory Integration

Memory integration determines how to use retrieved content efficiently. It can leverage techniques such as filtering, compression, and structured insertion to make the retrieved information easier and cheaper to use during generation.

Textual Integration.

When memory is stored as natural language, integration mainly means deciding which small set of text to show to the backbone model and in what format. DC-RS ([23]) integrates persistent memory by keeping a cheatsheet store, doing similarity-based retrieval, then synthesizing a compact cheatsheet that is inserted into the prompt.

Several agent-oriented systems follow the same idea but build on structured memory stores. In Mem0 ([37]), each memory item is a short natural language record with metadata (time, type, source, etc.). At inference time, the system retrieves the most relevant items and formats them as a compact memory block that is appended to the dialogue context, keeping only a handful of focused sentences in the prompt. Taking a more structured approach, A-MEM ([45]) organizes interaction history as Zettelkasten-style notes and uses a two-stage retrieval pipeline to select only a few high-utility notes; these notes are linearized into a small "working set" section inside the agent prompt, while the rest of the note graph remains offline. ACE ([46]) goes one step further and treats the agent context as an evolving playbook: it maintains a library of fine-grained strategy bullets with usage statistics, and before each episode it selects and injects only the most helpful bullets into the system instructions and memory prompts. Similarly, for execution efficiency, agentic plan caching ([38]) caches high-level plan templates distilled from successful past executions; at serving time, a cheap keyword-based matcher looks up a matching template and a small planner LLM adapts it to the new query, replacing a fresh planning phase with a short plan-adaptation prompt. Finally, apart from structured storage, general compression techniques are also employed to fit external information into the prompt. RECOMP ([32]) uses Retrieve–Compress–Prepend: an extractive compressor selects sentences and an abstractive compressor writes a short summary, which is prepended to the query; selective augmentation allows returning an empty string when retrieval is unhelpful.

Across these methods, textual memory integration improves efficiency by compressing long histories into task-specific snippets that fit into the prompt while retaining the main signals that drive agent behavior.

Latent Integration.

Latent memory integration stores long-term information as compact hidden states or key–value pairs and reuses them within the model’s internal computation, avoiding re-encoding the original text.

One approach to latent integration is to scale latent memory capacity while keeping the GPU KV cache roughly constant. MemoryLLM ([26]) inserts a trainable pool of memory tokens into every transformer layer. During inference these tokens are processed together with the normal sequence tokens, so information stored in the memory pool can influence the hidden states at each step without extending the visible context. Based on MemoryLLM, M+ ([27]) adds a CPU-resident long-term memory and a co-trained retriever that fetches a small set of relevant hidden-state memory tokens per layer during generation, enabling long-range recall with similar GPU memory overhead.

Alternatively, some latent integration methods maintain external knowledge or long context directly as compressed KV-level states, which are then integrated into the generation process via attention. Memory$^3$ ([28]) stores a KB as explicit key–value memory and, during decoding, retrieves a few entries per token block and adds their KVs to the attention KV cache, avoiding long prompts. MemoRAG ([25]) compresses long context into a KV-cache global memory over inserted memory tokens; a lightweight memory model generates a draft answer as a retrieval clue, This design reduces the query-time long-context cost by running full long-context inference on only a few selected passages, while the rest of the corpus is accessed through compressed KV-level memory.

Compared with purely textual integration, these latent mechanisms push most long-term information into fixed-size neural states and expose them through attention, so that the cost of using long-horizon experience grows much more slowly than the length of the raw interaction history.

3.4 Multi-Agent Memory

In LLM-based multi-agent systems (MAS), many early studies, such as CAMEL ([74]), mainly focus on textual communication protocols, where memory can typically be regarded as implicit and implemented in a simple form. More recent research has begun to explicitly focus on the notion of memory in MAS. These memory-oriented works still fit into the taxonomy proposed in our framework, but in this section we adopt a MAS-centered perspective and provide a more focused discussion of memory within multi-agent systems.

Shared Memory.

Shared memory centralizes reusable information across agents to mitigate redundancy, as duplicating multi-agent interaction histories in individual prompts is costly in both token budget and inference time.

MS ([60]) stores agent steps as Prompt–Answer pairs and filters them with an LLM evaluator before adding them to a shared pool, then uses accepted memories to continually refine the retriever. However, the frequent LLM-based scoring introduces substantial token and latency overhead.

To improve efficiency, recent work explores structured shared textual memory that supports lightweight retrieval and reduces redundant context replay.

G-Memory ([61]) models multi-agent experience as a three-tier graph hierarchy of insight, query, and interaction graphs; at inference, it performs bi-directional traversal to retrieve high-level, generalizable insights together with fine-grained, condensed interaction trajectories for agent-specific working memory. RCR-Router ([62]) maintains a Shared Memory Store of interaction history, task-relevant knowledge, and structured state representations, and performs round-wise context routing with an Importance Scorer, a Semantic Filter, and a Token Budget Allocator to minimize redundant context and token usage. MemIndex ([63]) adopts an intent-indexed bipartite graph architecture for memory operations in LM-based multi-agent pub/sub systems, improving storage, retrieval, update, and deletion efficiency and reporting lower elapsed time, CPU utilization, and memory usage. Different from typical shared-memory MAS that mainly consume retrieved context, MIRIX ([64]) adopts a modular multi-agent architecture governed by a Meta Memory Manager and six Memory Managers, and uses Active Retrieval to generate a topic and inject retrieved memories into the system prompt without explicit memory-search prompts.

Beyond textual shared memory, latent shared memory enables agents to exchange compact internal states, reducing redundant token-level replay. LatentMAS ([75]) implements latent shared memory by having each agent perform auto-regressive latent thinking from last-layer hidden states and consolidating the resulting layer-wise KV caches into a shared latent working memory for persistent read–write sharing across agents. KVComm ([76]) enables training-free online KV-cache communication by maintaining an anchor pool of shared segments and their KV offsets, then matching anchors and approximating offsets to safely reuse KV caches across new prefixes, avoiding repeated prefilling.

- **Advantages**: Enables cross-agent reuse of verified facts and decisions, improving coordination and efficiency by reducing redundant work and retries.

- **Disadvantages**: Prone to inconsistency from concurrent writes, and can become noisy and costly to retrieve without consolidation and access control.

Local Memory.

For local memory, redundancy accumulates within each agent as its personal store grows, so retrieval and updates should remain agent-local; meanwhile, local memory management can borrow ideas from single-agent methods such as selective writing, consolidation, and capacity control. Intrinsic Memory Agents ([65]) equips each agent with a role-aligned structured memory template and updates it every turn by folding the agent’s latest output back into the same template until consensus is reached. AgentNet ([66]) maintains fixed-size memory modules for the router and executor, and uses dynamic memory management with signals like frequency, recency, and uniqueness to prune low-utility trajectories at capacity. DAMCS ([67]) introduces A-KGMS, consolidating experiences into a goal-oriented hierarchical knowledge graph and planning via neighborhood queries around the most recent goal node to avoid full-history sharing and reduce overhead.

- **Advantages**: Lightweight, low-noise per-agent workspace that supports efficient retrieval and role-specific prompting.

- **Disadvantages**: Not shared across agents, so useful results may not propagate and work can be duplicated.

Mixed Memory.

Mixed memory combines shared and local memory, and its efficiency often benefits from coordination between the two, including what to write to each, when to retrieve from which, and how to control redundancy. SRMT ([68]) couples each agent’s personal memory vector with a shared recurrent memory by pooling all agents’ memory vectors and letting agents cross-attend to this shared sequence, then updating their personal vectors via a memory head. Collaborative Memory ([69]) uses dynamic bipartite access graphs with private/shared tiers, storing fragments with immutable provenance and enforcing sharing through configurable read/write policies. LEGOMem ([70]) builds modular procedural memory with full-task memories for the orchestrator and subtask memories for task agents, comparing vanilla retrieval with Dynamic and QueryRewrite variants for finer-grained subtask memory access.

- **Advantages**: Combines efficient per-agent local state with cross-agent knowledge reuse via shared memory, improving both specialization and coordination.

- **Disadvantages**: Adds synchronization and routing complexity, and can still suffer from inconsistency or noise in the shared store.

3.5 Discussion

Trade-off Between Memory Compression and Performance.

Although we have repeatedly emphasized that memory extraction can reduce costs such as input token usage, an unavoidable issue is that extraction may lead to the loss of critical information, which can directly degrade the agent's performance. This problem has also been noted in prior work such as AgentFold ([22]). LightMem ([59]), for instance, explicitly takes the compression rate into account. Its experimental results clearly show that excessive compression leads to poorer accuracy, whereas milder compression better preserves performance but incurs relatively higher cost. Therefore, how to strike an appropriate balance between compression and performance remains an open question, and there may also be alternative approaches that aim to retain as much salient information as possible during the extraction or compression process.

Online vs Offline Memory Management.

Regarding memory management strategies, A-MEM([45]) exemplifies a purely online system where memory updates occur synchronously during interaction. As demonstrated by MemoryOS([54]), such real-time updates incur frequent LLM calls per response, leading to higher latency and financial costs. By contrast, LightMem ([59]) adopts a hybrid architecture combining a lightweight online cache with offline consolidation. This design offloads expensive computations to asynchronous offline processes, significantly reducing inference time while maintaining similar overall computational costs. This comparison highlights a fundamental trade-off: online updates ensure immediate adaptation but increase latency and cost, whereas offline updates minimize inference overhead but suffer from slower adaptation. Consequently, this comparison suggests that an optimal memory system design should likely strike a balance between these two paradigms.

4. Efficient Tool Learning

\begin{tabular}{l|l|l|l}

\toprule

\textbf{Method} & \textbf{Category} & \textbf{Core Mechanism} & \textbf{Resource Link} \\

\midrule

\multicolumn{4}{c}{\textit{Efficient Tool Selection}}\\

\midrule

ProTIP [77] & External Retriever & Contrastive learning to correlate queries with tools & N/A \\

TinyAgent [78] & Multi-Label Classification & Implement a small model to select appropriate tools & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/SqueezeAILab/TinyAgent) \\

Tool2Vec [79] & Multi-Label Classification & Align tools with synthetic usage examples & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/SqueezeAILab/Tool2Vec) \\

ToolkenGPT [80] & Vocabulary-based Retrieval & Train tools as a special token & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/Ber666/ToolkenGPT) \\

Toolken+ [81] & Vocabulary-based Retrieval & Rerank top-k tools and reject if no one is selected & N/A \\

Chain-of-Tools [82] & Vocabulary-based Retrieval & Leverage CoT with a huge tool pool & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/fairyshine/Chain-of-Tools)\\

ToolGen [83] & Vocabulary-based Retrieval & Encode each tool as a separate token & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/Reason-Wang/ToolGen) \\

\midrule

\multicolumn{4}{c}{\textit{Efficient Tool Calling}}\\

\midrule

Toolformer [84] & In-Place Parameter Filling & Leverage CoT to invoke tool calls & N/A \\

CoA [85] & In-Place Parameter Filling & Uses symbolic abstractions for intermediate steps & N/A \\

LLMCompiler [86] & Parallel Tool Calling & A compiler-inspired framework enabling parallel tooling & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/SqueezeAILab/LLMCompiler)\\

LLM-Tool Compiler [87] & Parallel Tool Calling & Fusing similar tools and parallel tooling & N/A \\

CATP-LLM [88] & Parallel Tool Calling & Include cost-awareness into planning & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/duowuyms/OpenCATP-LLM) \\

BTP [89] & Cost-Aware Tool Calling & Formulates tool calling as a knapsack problem & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/THUNLP-MT/BTP) \\

TROVE [90] & Cost-Aware Tool Calling & Introduce compact reusable tools. & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/zorazrw/trove) \\

ToolCoder [91] & Cost-Aware Tool Calling & Treat tool as code generation & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/dhx20150812/ToolCoder) \\

ToolChain* [92] & Test-Time Scaling & Utilizes A* search to prune unproductive branches & N/A \\

OTC-PO [93] & Post-training / RL & Integrates tool-use penalty into RL objective & N/A \\

ToolOrchestra [94] & Post-training / RL & Efficiency-aware rewards for specialized orchestrators & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/NVlabs/ToolOrchestra/) \\

\midrule

\multicolumn{4}{c}{\textit{Tool-Integrated Reasoning (TIR)}}\\

\midrule

TableMind [95] & Adaptive Search & Plan-action-reflect loop with Rank-Aware Optimization & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/lennendd/TableMind) \\

SMART [96] & Boundary Awareness & CoT-based dataset to decide parametric vs. tool use & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/qiancheng0/Open-SMARTAgent) \\

ARTIST [97] & Policy Optimization & Unified agentic reasoning with outcome-based RL & N/A \\

AutoTIR [98] & Policy Optimization & Hybrid reward for correctness and format adherence & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/weiyifan1023/AutoTIR) \\

ReTool [99] & Code-Integrated Reasoning & Dynamic NL-code interleaving with verifiable rewards & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/ReTool-RL/ReTool) \\

ToolRL [100] & Structured Rewards & Combines format reward with tool parameter correctness & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/qiancheng0/ToolRL) \\

PORTool [101] & Step-wise Planning & Uses fork-relative advantages and decay factors & N/A \\

Agent-FLAN [102] & Data Efficiency & Decomposes agent data into capability-specific subsets & \faIcon{github}\, [GitHub](https://github.com/InternLM/Agent-FLAN) \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

Tool learning provides an interface for LLMs to interact with the physical world and virtual environment. In general, tools refer to search, code sandbox (interpreter), and many other general API endpoints. To call these tools, a basic solution is to provide several candidates to the prompt, and let the LLM think and select the most suitable one with parameters filled [103]. However, as the task become more complex, there would be much more tool calls. For example, LLMs may call the search API for 600 times to resolve a deep research problem [104]. Such long trajectories extremely challenge the models' long context comprehension ability and brings enormous costs. To this end, it is crucial to explore efficient tool learning strategies.

Overall, there are two types of efficiency in tool learning: (1) Tool learning itself is efficient for solving complex problems. Comparing with a task with very long CoT, tool learning could efficiently optimize the length of trajectories and show the efficient reasoning process. (2) Tool learning could be optimized to call fewer tools, which reduces the cost of tool learning itself. For a complex task with hundreds of tool calls, an optimal method could significantly reduces the number of tool calls. So the overall process would be even more efficient.

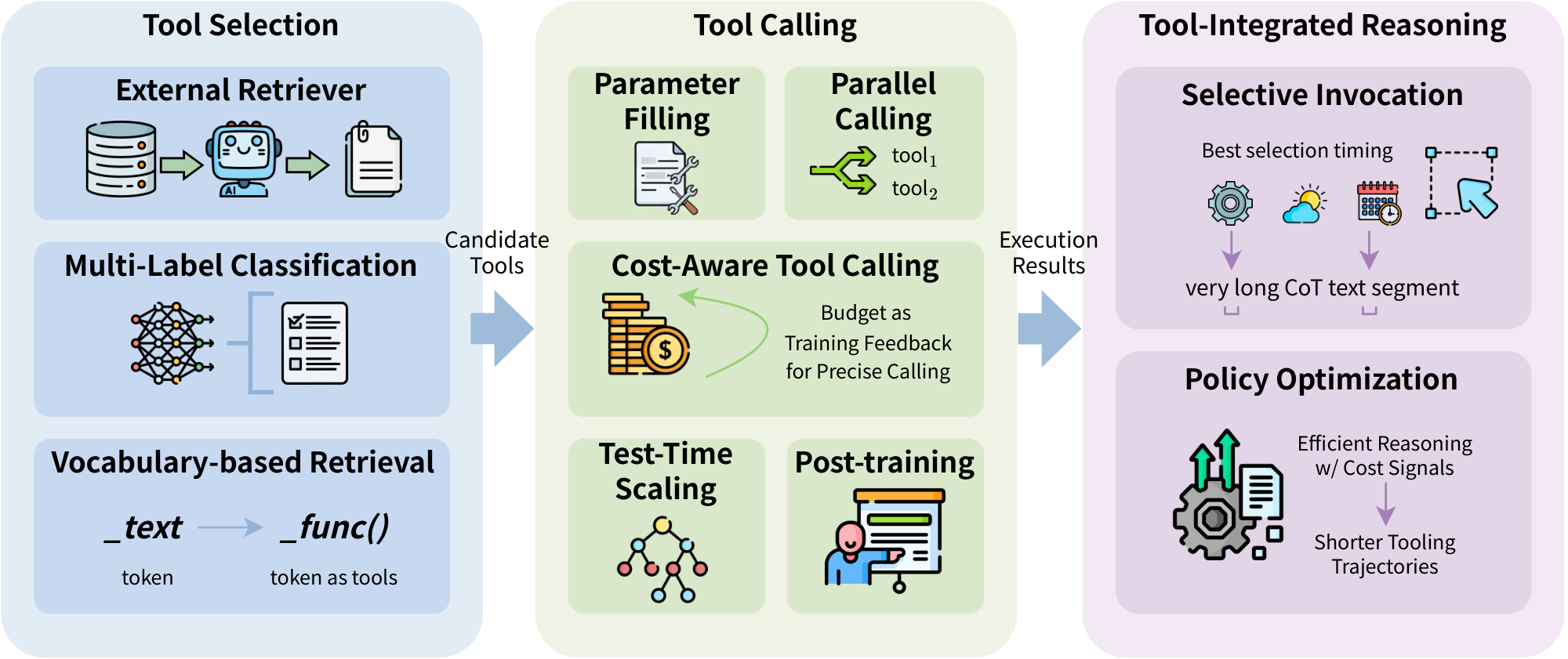

As shown in Figure 4, we introduce efficient tool learning in three main categories, including Tool Selection, Tool Calling, and Tool-Integrated Reasoning. Candidate tools are first selected to let LLM judge when and what to call, then the tool call's results would be embeded into the response and the reasoning trajectories.

4.1 Tool Selection

For massive tool candidates from a very large pool, it is nearly impossible to stuff the prompt with thousands of tool descriptions. To this end, it is crucial to efficiently select the most relevant tools for user queries. We organize current tool retrieval literature into three categories: (1) External Retriever: a independent retriever model which embeds user queries and tool descriptions and calculates the affinity scores (e.g. cosine similarity) to select top- $k$ relevant tools as candidates; (2) Multi-Label Classification: for a fixed size of tool sets, the tool selection process could be formulated as a multi-label classification problem, which directly predicts relevant tools; and (3) Vocabulary-based Retrieval: tools are embedded as special tokens into the model's vocabulary, and the model would enter a tool call mode when generating such tool tokens. We introduce the above three categories of tool selection strategies in this section as below.

External Retriever.

Instead of including the entire tool set, many approaches rely on an external retriever for tool selection. External tool retrieval can be improved from retriever-side advances that redesign the retrieval pipeline or strengthen retrievers and rerankers, and from tool-side enhancements that refine tool descriptions and documentation to make the retrieval corpus easier to match, boosting both accuracy and efficiency.

On the retriever side, ProTIP [77] utilizes a contrastive learning-based method to embed user queries and tool descriptions into the semantic space. After a tool is selected, ProTIP subtracts the query embedding by the selected tool's representation and selects tools on other subtasks. Such a progressive design makes ProTIP efficient to avoid explicit task decomposition overhead. In AnyTool ([105]), retrieval is organized hierarchically and inspired by a divide-and-conquer strategy, narrowing the search space and thereby improving retrieval efficiency.

On the tool side, DRAFT ([106]) refines tool documents via self-driven interactions to improve external tool retrieval, while boosting efficiency by reducing token overhead and stopping refinement at convergence.

In addition, some recent systems combine both directions. Toolshed ([107]) stores enriched tool representations in a tool knowledge base and uses RAG-tool fusion before, during, and after retrieval to scale external tool selection, while controlling top-k to curb token growth and improve efficiency. Similarly, ToolScope ([108]) uses ToolScopeMerger with Auto-Correction to compress tool descriptions and reduce input tokens, and ToolScopeRetriever to hybrid-retrieve top-k tools that fit the LLM context window, improving tool-use quality while boosting efficiency and scalability.

Multi-Label Classification (MLC).

Instead of ranking-based retrieval, MLC-based methods treat tool selection as a classification task. TinyAgent [78] is designed to conduct tool calling on edge devices which pursue extreme efficiency, and it formulates the tool selection task as a multi-label classification problem. For a user query, TinyAgent applies the DeBERTa-v3 small model as the encoder and output the probability distribution for all available tools. Tools with a probability higher than 50% are recognized as relevant ones and will be selected accordingly. Since only a small fraction of tool descriptions are put into the prompt, it efficiently reduces nearly half of the prompt size. Similar to TinyAgent, [79] find MLC-based tool retrieval efficient, but such a task formulation could not handle the growing number of tools, and any updates would require a model re-training. Therefore, they propose Tool2Vec, a two-stage retrieval with a reranker for analyzing fine-grained tool-query interactions. To fill in the semantic gap where natural user queries may not directly align with tool descriptions, the authors generate tool embeddings based on synthetic usage examples rather than static description.

Vocabulary-based Retrieval.

Besides direct retrieving from candidates by external retriever and MLC, tool selection could also be formulated as a token prediction task, where tools are stored in the vocabulary as special tokens.

ToolkenGPT [80] regards massive external tools as learnable token embeddings (aka. "toolken"), so that the target tool could be selected as a normal next token prediction process. Compared with Toolformer [84] that selects tools by predicting a whole trajectory with special characters, this approach is highly efficient since it only trains the added tool embeddings and keeps other model parameters frozen. Furthermore, it bypasses the window constraint of in-context tool selection and retains a shorter prompt. Building on this foundation, Toolken+ [81] enhances ToolkenGPT by introducing an extra reranking step and a rejection toolken, which improves the overall performance and reduces the hallucination rate. Toolken+ also demonstrates a tradeoff between efficiency and efficacy, which could be simply tuned from the number of reranking candidates. Although "toolkens" are efficient for massive tool selection, it requires constructing data samples for supervised fine-tuning and suffers from generalization problems on unseen tools. Similarly, ToolGen ([83]) assigns each tool a unique tool token and trains the model to turn tool retrieval and calling into a unified generation task. By representing a tool with a single token, it is claimed to shorten generation and potentially reduce inference overhead but may be costly at training phase. From a different perspective on efficiency, [109] proposes selective compression and block compression for tool use: they preserve key information (e.g., tool and parameter names) as raw text while compressing the remaining documentation into fixed-length soft tokens per block. The soft tokens can be precomputed and cached offline, reducing prompt length and improving token efficiency at inference. To tackle the generalization problem, CoTools [82] shrinks the number of toolkens to only one and applies a retriever to calculate the similarities between current toolken's representation and all the candidates.

From these literature, we find vocabulary-based methods are an efficient option for tool selection. However, it may suffer from inaccurate invocation timing and poor generalization to unseen new tools, which is less functional for extensive tool updating scenarios.

- **Advantages**: External retriever, MLC, and vocab-based methods are very efficient especially for retrieval from massive candidates. External retriever could be a plug-and-play module with a good generalization ability to unseen tools.

- **Disadvantages**: The external retriever may be a large model with more computational overhead than MLC and vocab-based tool tokens, while MLC and vocab-based tool retrieval may need fine-tuning to adapt models on new tools.

- **Applicable scenarios**: According to the types of candidate tools, if the candidate pool changes a lot over time, it would be better to use external retrievers. However, if the candidate tool set is relatively fixed, MLC and vocab-based methods are good options for better efficiency.

4.2 Tool Calling

Once candidates are selected, the efficiency of the invocation process becomes critical for real-time agentic interactions.

In-Place Parameter Filling.

In-place tool calling is a paradigm where the model directly fills the tool's parameters during the response generation process. Toolformer [84] incorporates tool calling within the CoT path, and fills parameters during the response generation process. It is efficient to obtain the final results once the closure of the tool call is reached. [85] proposes CoA, which shares the similar idea but reduces the response time by providing more accurate tool call results. Instead of directly calculating the final results, CoA introduces symbolic abstractions to represent the intermediate steps, which are later substituted with the actual results during the response generation process. From the experimental results, CoA performs better while reducing more than 30% inference time than Toolformer.

Parallel Tool Calling.

For a complex tasks that incorporates multiple tools, traditional sequential style calling may hurt efficiency since LLMs have to wait for the latest tool call's response. However, there are multiple tasks that could be done in parallel [110]. For example, to get the weather information of a province, we do not have to call the get_weather API one-by-one for each city. Instead, a more practical way is to make parallel tool calls, which would significantly reduce the overall task solving time. LLMCompiler [86] introduces a compiler-inspired framework that formulates execution plans, dispatches tasks, and executes functions in parallel. This achieves improvements in latency, cost, and overall accuracy against the traditional sequential tool execution approach. Building on this parallelization paradigm, LLM-Tool Compiler [87] further optimizes efficiency by selectively fusing similar tool operations at runtime, which increases parallel tool calls while reducing token consumption and latency. Complementing with the above methods, CATP-LLM [88] addresses the execution cost by incorporating cost-awareness into the planning process. It designs a multi-branch planning language and employs cost-aware offline reinforcement learning to fine-tune models, enabling high-quality generation with economic constraints.

Cost-Aware Tool Calling.

Like we have introduced about CATP-LLM in the above paragraph, cost could be a special reward for training efficient tool calling models. Budget-Constrained Tool Learning with Planning (BTP) [89] first formulates tool calling as a knapsack problem, which utilizes dynamic programming to pre-compute how often each tool would be invoked under a hard budget, thereby turning cost control into a forward-looking plan. Building on this planning strategy, [111] estimates LLM confidence via consistency-based sampling strategy to let the model trigger a tool under a certainty-cost optimal condition. This method could reduces the number of tool calls, thereby boosting the overall improvements. From a broader system perspective, [112] reduces redundant calls by jointly updating prompt strategy and tool documentations. It complements the above cost-aware planning and confidence-based gating with context-level efficiency.

Beyond directly constraining invocation budgets, recent research also explores improving efficiency through alternative paradigms, such as function induction, code generation, and model distillation. TROVE [90] introduces a training-free paradigm that incrementally builds and trims a compact toolbox of reusable functions, showing that online induction can improves the accuracy without extra training data. ToolCoder [91] extends this idea by formulating tool learning as an end-to-end code generation task, which converts tasks in natural languages into Python code. This method boosts the success rates while keeping small API usage cost. Focusing on the deployment cost, [113] proposes to distill LLM's knowledge into small language models with retrieval and code interpreter tools, which enables small models competitive with larger ones.

Efficient Test-Time Scaling.

For effective tool calling, a viable solution is tree search-based strategies, where the model may plan a tree of tool calls and select the most promising path [114].

However, such methods are computationally expensive since they may need trail-and-error to explore the entire tree. Instead of extensive tree traversal, ToolChain* [92] utilizes the A* search strategy to efficiently navigate complex action spaces. This method boosts the efficiency by employing task-specific cost functions to prune wrong branches earlier and only requires single-step node expansions. Therefore, it allows the agent to prioritize the most promising paths and avoids exhaustive searches, leading to high success rates.

Efficient Tool Calling with Post-training.

To mitigate the high latency and computational overhead with multi-step tool interactions, recent research has increasingly focused on optimizing tool-calling efficiency through post-training. Specifically, reinforcement learning has emerged as a primary mechanism for teaching models to strategically balance task success with resource parsimony. OTC-PO [93] promotes action-level efficiency by integrating a tool-use penalty into the reinforcement learning objective, which effectively trains models to minimize redundant tool calls without sacrificing answer correctness. Building on the optimization of agentic workflows, ToolOrchestra [94] leverages efficiency-aware rewards within an RL framework to train specialized orchestrators that achieve superior task performance at a fraction of the computational cost of general-purpose large language models. Complementing these strategy-driven approaches, ToolRM [115] addresses the challenge of precise evaluation by utilizing specialized outcome-based reward models to facilitate data-efficient fine-tuning and inference-time scaling, ensuring that models learn to prioritize the most effective and concise tool-calling trajectories.